What is Bell’s palsy?

Bell’s palsy is sudden, temporary weakness or paralysis on one side of the face. It happens when the facial nerve - the seventh cranial nerve - becomes inflamed and compressed inside a narrow bony tunnel called the fallopian canal. You might wake up one morning with your mouth drooping, difficulty closing your eye, or trouble smiling. It’s not a stroke, and it’s not caused by a tumor or injury. In most cases, doctors can’t find a clear reason why it happens - which is why it’s called idiopathic facial nerve paralysis.

It affects about 15 to 30 people out of every 100,000 each year. The peak age range is between 15 and 45. While it can happen to anyone, pregnant women, people with diabetes, and those with upper respiratory infections are at slightly higher risk. The good news? Most people recover fully, but not everyone does - and timing matters a lot.

Why corticosteroids are the first-line treatment

If you’re diagnosed with Bell’s palsy, the single most important thing your doctor will likely prescribe is a course of corticosteroids - usually prednisone. This isn’t a guess. It’s backed by high-quality evidence from dozens of clinical trials reviewed by Cochrane and the American Academy of Family Physicians.

Without treatment, about 70% of people recover fully within a few months. But with corticosteroids, that number jumps to 85-90%. That’s a big difference. The key is reducing swelling around the facial nerve. When the nerve swells inside its tight bony canal, it gets squished. That’s what causes the paralysis. Corticosteroids cut that swelling fast, giving the nerve room to heal.

The evidence is clear: corticosteroids reduce the chance of incomplete recovery by about 31%. That means for every 10 people treated, one person avoids lasting facial weakness. That’s why major medical groups - including the American Academy of Neurology and the American Academy of Otolaryngology - all agree: start corticosteroids as soon as possible.

The right dose and timing

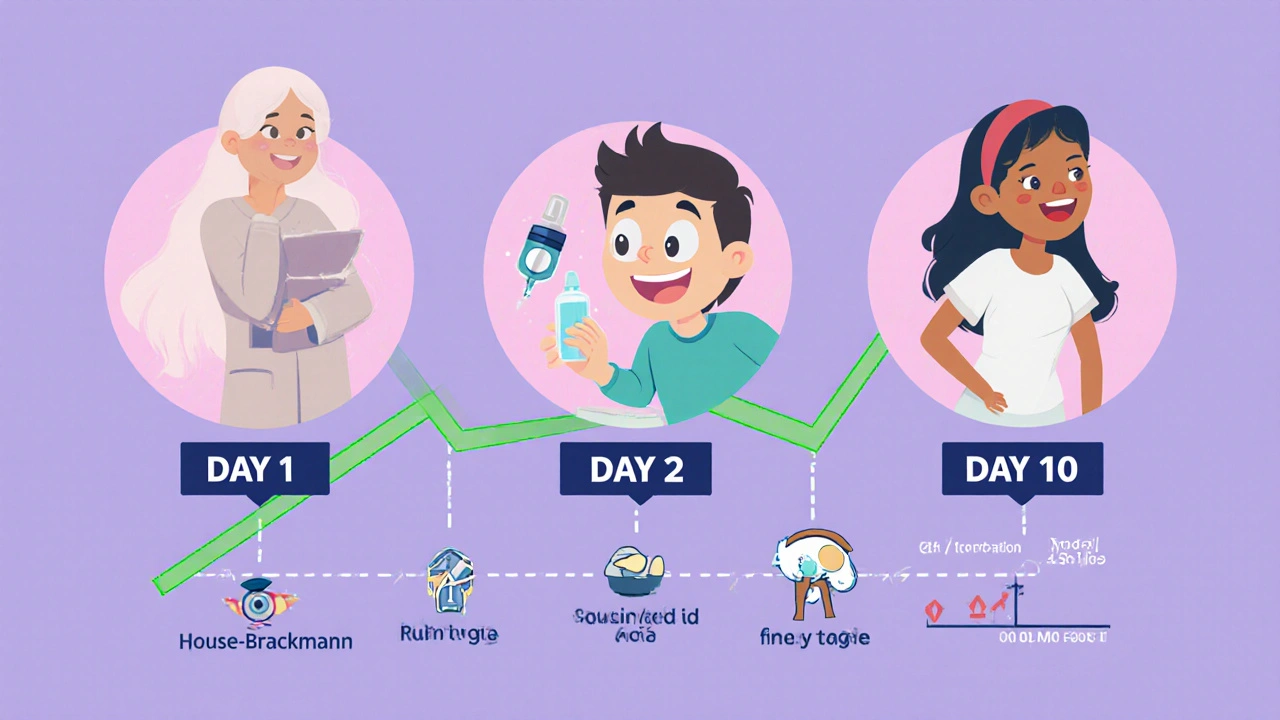

Not all steroid treatments are created equal. The standard, proven regimen is 50 to 60 milligrams of prednisone daily for five days, followed by a five-day taper down to zero. That’s a total of 500 milligrams over 10 days. This exact schedule is based on data from over 800 patients in randomized trials.

Here’s what the research shows: if you take less than 450 milligrams total, your chance of incomplete recovery is around 30%. But if you take 450 milligrams or more, that drops to just 14%. Dose matters. Skipping days or cutting the course short reduces effectiveness.

Timing is even more critical. The window for maximum benefit is within 48 hours of symptoms starting. Some benefit remains if you start within 72 hours, but after that, the effect fades fast. Many people delay seeing a doctor because they think it’s a stroke or a sleep position issue. That’s why it’s so important to act fast - even if you’re unsure. If your face suddenly droops, don’t wait. Go to a clinic or ER. A quick exam can rule out stroke and confirm Bell’s palsy.

What about antivirals?

You might hear about using antivirals like acyclovir or valacyclovir with steroids. That’s because some believe Bell’s palsy is triggered by the herpes virus. But here’s the truth: antivirals alone don’t help. Multiple studies show no improvement in recovery when antivirals are used by themselves.

When combined with corticosteroids, the results are mixed. Some studies suggest the combo might reduce the risk of synkinesis - that’s when facial muscles move abnormally during recovery, like your eye squints when you smile. But it doesn’t significantly improve overall recovery rates. The American Academy of Family Physicians gives this combo a moderate evidence rating (B), saying it “should be considered” mainly to reduce long-term awkward movements, not to speed up healing.

There’s one exception: Ramsay Hunt syndrome. That’s when the virus causes Bell’s palsy plus a painful rash around the ear. In that case, antivirals are essential. But that’s not Bell’s palsy - it’s a different condition. Doctors can tell the difference by looking for the rash.

Side effects? Mostly harmless

People are scared of steroids. They think of weight gain, mood swings, or diabetes flare-ups. Those are real risks - but only with long-term use. A 10-day course of prednisone? The side effects are mild and temporary.

In clinical trials, the rate of side effects in people taking prednisone was almost identical to those taking a placebo. The most common issues reported were trouble sleeping, increased appetite, and a slight mood change. No serious side effects like infections or high blood pressure were linked to the treatment in these short-term studies.

One important note: if you have diabetes, your blood sugar might rise during the course. You’ll need to check it more often. But for most people, the risks are tiny compared to the benefit of avoiding permanent facial weakness.

What doesn’t work

There are a lot of alternative treatments out there. Low-level laser therapy. Hyperbaric oxygen. Injections into the ear. Stellate ganglion blocks. Some clinics even offer acupuncture.

The evidence? None of these have been proven better than corticosteroids in high-quality studies. A 2023 review of 32 trials found no reliable data showing any of these methods improve recovery rates. Some might make people feel better temporarily - maybe because of placebo or relaxation - but they don’t change the nerve’s healing process.

And while it’s tempting to try anything when your face looks different, sticking to the proven treatment is your best bet. The goal isn’t to try everything - it’s to do what works.

Recovery and follow-up

Most people start to see improvement within two to three weeks. Full recovery usually takes three to six months. But recovery isn’t always perfect. About 10-15% of people have some lasting weakness, like a slight droop or involuntary movements.

Doctors use the House-Brackmann scale to track progress. It grades facial movement from I (normal) to VI (complete paralysis). Most patients start at grade IV or V and improve over time. If you’re not getting better after three months, you should see a neurologist or facial nerve specialist. They might recommend physical therapy or further testing to rule out other causes.

Eye care is critical during recovery. If you can’t close your eye, it can dry out and get damaged. Use artificial tears during the day and lubricating ointment at night. Taping the eye shut while sleeping is a simple trick that prevents corneal ulcers.

Why early diagnosis saves faces

One of the biggest problems with Bell’s palsy is misdiagnosis. About 15-20% of cases are initially mistaken for something else - stroke, Lyme disease, tumor, or even a dental issue. That’s dangerous because stroke needs emergency treatment. Bell’s palsy doesn’t.

Key signs that it’s likely Bell’s palsy: sudden onset (hours), no other neurological symptoms (like arm weakness or slurred speech), and full facial involvement (forehead, eye, mouth). If you can’t raise your eyebrow on one side, it’s probably Bell’s palsy. If you can, it’s more likely a stroke.

Telemedicine tools are now helping people get faster assessments. Some apps let you record your face and use AI to flag signs of paralysis. In pilot programs, this has cut the time to treatment by over 40%. If you’re unsure, take a video of your face smiling, blinking, and raising your eyebrows. Show it to your doctor. It helps.

What’s next for Bell’s palsy treatment?

Research is moving toward personalization. A 2023 machine learning study of nearly 500 patients found that age and corticosteroid use were the two strongest predictors of recovery. Younger people recover better. Those who get steroids early recover best.

Future studies are looking at biomarkers - things in the blood or nerve fluid - that could tell us who will respond best to steroids. There’s also interest in whether higher doses or longer courses help people with severe paralysis (House-Brackmann grade V or VI).

For now, the treatment hasn’t changed much since the 1980s. But the evidence behind it has never been stronger. Corticosteroids are cheap, safe, effective, and backed by decades of research. The challenge isn’t finding a better drug - it’s getting people to start it fast enough.

Nicole Ziegler

This is the kind of post that makes me actually trust medical advice on the internet. 🙌 I had Bell’s palsy last year and my doctor didn’t even mention steroids until day 4. Wish I’d seen this sooner.

Bharat Alasandi

Dose matters. 500mg total is the sweet spot. Less than that and you're basically just doing yoga and hoping. I've seen too many patients skip the taper and wonder why they relapsed.

Shiv Karan Singh

Corticosteroids? LOL. Big Pharma’s favorite cash grab. Ever heard of turmeric or acupuncture? Real medicine doesn't come in pills. 😏

Summer Joy

SHOCKING. 😱 I had Bell’s palsy and did BOTH steroids AND acupuncture. My face looks like a Picasso painting now. So... maybe the steroids didn’t work? Or maybe I’m just cursed? 🤷♀️

Kristi Bennardo

This post is dangerously misleading. Corticosteroids are immunosuppressants. You're telling people to take a powerful drug for a condition that 'often resolves on its own'? That’s medical malpractice waiting to happen.

Michael Fessler

I’m a neurologist. Just wanna say: the 48-hour window is real. We had a patient come in at 72 hours - she recovered, but with synkinesis. At 36 hours? Perfect recovery. Time = nerve integrity.

Matthew Karrs

Of course they say steroids work. The FDA’s got ties to Big Pharma. Did you know prednisone was originally developed for military use? They just repackaged it as a 'cure' for face droop. 🤔

Matthew Peters

I didn’t believe this until it happened to me. Woke up looking like a sad pug. Went to urgent care. Got steroids. 3 weeks later, I was back to normal. I’m not religious, but I’m gonna pray to the steroid gods every morning now.

Liam Strachan

I'm from the UK and we’ve had the same guidelines for years. It’s nice to see the evidence being laid out so clearly. I’ve sent this to my sister - she’s worried about her face right now.

Aruna Urban Planner

The real tragedy isn't the facial paralysis - it's the delay in care. In rural India, many wait weeks before seeing a doctor. The science is clear, but access isn't. We need community health workers trained to recognize Bell’s palsy. Not just pills - systems.

Ravi boy

i had this last year and my uncle said put onion on face lol i did it for 3 days and nothing happened then i went to doc and got prednisone and boom 2 weeks better

daniel lopez

You’re all being manipulated. Bell’s palsy is caused by 5G radiation and glyphosate. Steroids just mask the symptoms while the real enemy - the corporate-government-military complex - laughs all the way to the bank. Wake up.

Gerald Cheruiyot

The body heals itself. Medicine just removes obstacles. Steroids reduce swelling. That’s all. No magic. Just biology. And timing. And knowing when to act. Simple. Not sexy. But true.

Nosipho Mbambo

I'm from South Africa, and we don't even have access to prednisone in some clinics. So... what do we do? Wait? Hope? Pray? This post is great, but it's for people who can actually get care. Where's the equity in this?