Potassium Management Calculator for Heart Failure Patients

This calculator helps determine appropriate potassium management strategies for heart failure patients on diuretics based on current potassium levels. The safe range for heart failure patients is 3.5-5.5 mmol/L.

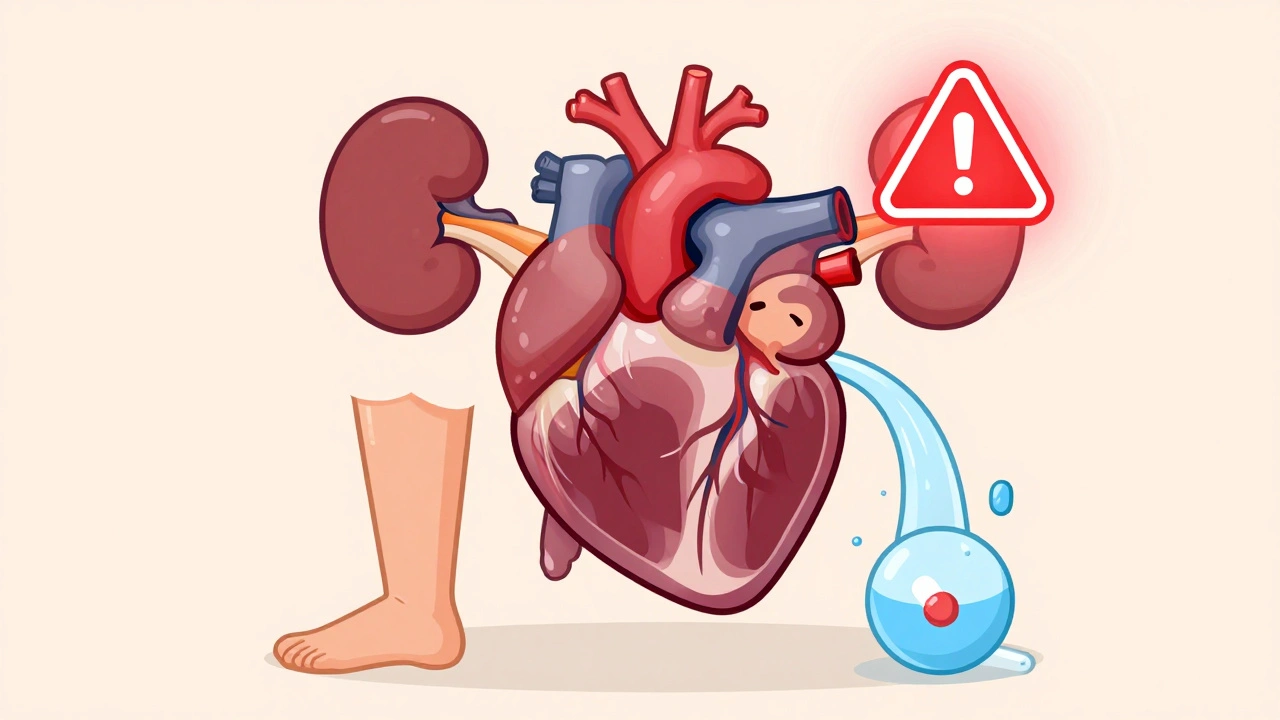

When someone has heart failure, fluid builds up in the body - lungs, legs, abdomen. Diuretics, especially loop diuretics like furosemide, are the go-to treatment to flush that excess fluid out. But there’s a hidden risk: hypokalemia, or dangerously low potassium levels. It’s not just a lab number. It’s a trigger for irregular heartbeats, hospital readmissions, and even sudden death.

Studies show about 20-30% of heart failure patients on loop diuretics develop hypokalemia. That’s not rare. It’s common. And it gets worse with higher doses, poor diet, or when other meds like laxatives or thiazides are added. The goal isn’t just to remove fluid - it’s to do it without tipping the body into electrical chaos.

Why Low Potassium Is Dangerous in Heart Failure

Potassium isn’t just for muscle cramps. It’s what keeps your heart beating regularly. In heart failure, the heart is already weakened. Add low potassium, and the risk of dangerous arrhythmias - like ventricular tachycardia or torsades de pointes - jumps by 1.5 to 2 times. That’s not a small uptick. That’s life-or-death.

Patients with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) are especially vulnerable. Their hearts are stretched thin, and their kidneys are working overtime to compensate. Diuretics push more sodium and water out, but they also push out potassium. The result? A ticking time bomb in the bloodstream.

And here’s the twist: even mild hypokalemia - potassium between 3.0 and 3.5 mmol/L - carries risk. Many doctors think, “It’s just a little low,” but that’s when the real damage starts. The 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guidelines say the safe range for heart failure patients is 3.5-5.5 mmol/L. Stay outside that, and complications climb.

How Diuretics Drain Potassium

Loop diuretics work in the kidney’s loop of Henle. They block the Na-K-2Cl transporter, which sounds technical, but here’s what it means: more sodium ends up in the urine. To balance that, the kidney pulls potassium out too - through channels in the collecting duct. The more diuretic you give, the more potassium you lose.

But it’s not linear. There’s something called within-dose diuretic tolerance. After the first dose, the body starts holding onto sodium again. So doctors often double the dose - and with it, potassium loss. Giving furosemide once a day? Big spikes in potassium loss. Splitting the same dose into two - say, 40 mg in the morning and 40 mg at noon - smooths out the effect. Less crash, less potassium drop.

And don’t forget: salt restriction helps reduce fluid overload, but it backfires on potassium. Less sodium means the body ramps up aldosterone - a hormone that says, “Keep sodium, flush potassium.” So even patients eating clean can still crash their potassium levels.

First-Line Fix: Potassium-Sparing Medications

The best way to prevent hypokalemia isn’t to stop diuretics - it’s to add potassium-sparing drugs. Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) like spironolactone and eplerenone do exactly that.

Spironolactone, at 12.5-25 mg daily, doesn’t just help with potassium. The landmark RALES trial showed it cuts death risk by 30% in severe heart failure. Eplerenone works similarly, with fewer side effects like gynecomastia. These aren’t add-ons. They’re essential.

Guidelines now recommend MRAs for all HFrEF patients unless potassium is already above 5.0 mmol/L or kidney function is too poor. Even if potassium is normal at first, start low and monitor. Don’t wait for it to drop.

And here’s something new: SGLT2 inhibitors - drugs like dapagliflozin and empagliflozin - are now part of standard care. Originally for diabetes, they’ve been shown to reduce hospitalizations in both HFrEF and HFpEF. Crucially, they reduce diuretic needs by 20-30% and don’t mess with potassium. In fact, they may slightly raise it. That’s rare in heart failure meds. Use them early.

When to Use Oral or IV Potassium

If potassium drops below 3.5 mmol/L, you need to replace it. But how?

- Mild hypokalemia (3.0-3.5 mmol/L): Oral potassium chloride. Start with 20-40 mmol per day, split into two doses. Avoid liquid forms if the patient has nausea - they’re hard to keep down. Tablets or extended-release capsules are better.

- Severe hypokalemia (<3.0 mmol/L): IV replacement. Give 10-20 mmol per hour, never faster. Always monitor with an ECG. Sudden IV pushes can cause cardiac arrest. Don’t rush.

Never give potassium without checking kidney function. If eGFR is below 30, IV potassium becomes risky. In those cases, focus on stopping potassium-wasting meds and using MRAs instead.

Also, check for hidden causes. Is the patient taking laxatives? Are they skipping meals? Are they on corticosteroids? These are often overlooked.

Dosing and Timing Matter

Many patients get one daily dose of furosemide - say, 80 mg at 8 a.m. That leads to a huge spike in urine output, then a crash by evening. The body rebounds. Sodium comes back. Potassium keeps draining.

Try splitting the dose. Furosemide 40 mg at 8 a.m. and another 40 mg at 2 p.m. This keeps the diuretic effect steady. Less rebound. Less potassium loss. It’s simple, cheap, and backed by data from the 2020 JACC review.

For patients on high-dose diuretics, adding a low-dose thiazide like metolazone (2.5 mg) can boost fluid removal. But it also increases potassium loss. So only use it if you’re already on an MRA and monitoring closely. Never use thiazides alone in heart failure.

Monitoring: When and How Often

Checking potassium isn’t optional. It’s mandatory.

- When starting or changing diuretics: check potassium within 3-7 days.

- After hospital discharge for heart failure: check at 1 week, then monthly if stable.

- During acute decompensation: check every 1-3 days.

Don’t wait for symptoms. Weakness, palpitations, or constipation might show up - but by then, the damage is already happening. Routine labs are your shield.

Also track eGFR and BNP. Rising BNP means fluid is still building. Falling eGFR might mean you’re over-diuresing. Both affect potassium. Use them together.

What to Avoid

Some practices still linger - and they’re dangerous.

- Don’t stop diuretics just because potassium is low. Fluid overload kills faster than mild hypokalemia. Fix the potassium, not the diuretic.

- Don’t use potassium supplements without monitoring. Too much potassium can be just as deadly as too little.

- Don’t ignore HFpEF. These patients often get less aggressive treatment, but they still lose potassium. Their kidneys react differently - and they’re more prone to sudden death from arrhythmias.

- Don’t assume dietary potassium is enough. Bananas, spinach, and potatoes help - but they won’t fix a 2.8 mmol/L level. Medication is needed.

The Future: Smarter, Personalized Care

Heart failure management is shifting from one-size-fits-all to precision care. New tools are emerging:

- Biomarker-guided dosing: Using BNP or NT-proBNP to adjust diuretic doses. Early data shows this cuts hypokalemia by 15-20% compared to standard dosing.

- Extended-release diuretics: Still in trials, but they promise smoother, all-day fluid removal - less potassium fluctuation.

- Potassium binders: Like patiromer or sodium zirconium cyclosilicate. These are used for high potassium, but future use may include fine-tuning levels in both directions.

The bottom line: diuretics save lives. But they’re not harmless. Managing potassium isn’t an afterthought - it’s part of the treatment plan from day one.

Can I just eat more bananas to fix low potassium from diuretics?

No. While foods like bananas, spinach, and potatoes contain potassium, they won’t raise levels fast enough if they’re below 3.5 mmol/L. Oral potassium supplements or potassium-sparing medications are needed for clinical hypokalemia. Diet helps as a support, not a cure.

Are all diuretics equally likely to cause low potassium?

No. Loop diuretics (furosemide, torsemide) and thiazides (hydrochlorothiazide) are the biggest culprits. Potassium-sparing diuretics like spironolactone and amiloride don’t lower potassium - they help keep it up. Always pair potassium-wasting diuretics with a potassium-sparing agent in heart failure.

Why do some heart failure patients get high potassium instead of low?

That usually happens when patients are on ACE inhibitors, ARBs, or MRAs - especially if kidney function is poor. It’s not the diuretic causing it. It’s the combination of RAAS blockers and reduced kidney clearance. The key is balance: monitor potassium regularly and adjust meds accordingly.

Should I stop my diuretic if my potassium is low?

Never stop a diuretic without medical advice. Fluid overload in heart failure can cause respiratory failure or sudden death. Instead, add potassium replacement or a potassium-sparing medication. The goal is to manage both fluid and electrolytes together.

How often should I get my potassium checked on diuretics?

Check within 3-7 days after starting or changing your diuretic dose. Once stable, monthly checks are usually enough. But if you’re sick, hospitalized, or on multiple heart meds, check every 1-3 days until stable.

Managing heart failure isn’t about one drug. It’s about balance - fluid, potassium, kidney function, and symptoms. Diuretics are powerful, but they need partners. Use them wisely, monitor closely, and don’t treat low potassium as a side effect - treat it as a signal.

Vivian Amadi

This post is basically a textbook chapter disguised as a Reddit thread. Loop diuretics aren’t ‘dangerous’-they’re *necessary*. But if you’re not monitoring potassium like a hawk, you’re not just negligent, you’re reckless. I’ve seen patients code because their doc thought ‘3.2 is fine.’ NO IT’S NOT. Stop pretending hypokalemia is a minor hiccup. It’s a silent killer.

Jimmy Kärnfeldt

Really appreciate this breakdown. It’s easy to get caught up in just pushing fluid out, but the heart’s electrical system is so delicate. I’ve had patients tell me they felt ‘off’ for days after a diuretic dose change-and no one ever connected it to potassium. This is the kind of stuff that saves lives, not just lab values. Thanks for writing it.

Ariel Nichole

Love the point about splitting the furosemide dose. So simple, but so many docs still give it all at once. I started doing this with my patients last year and saw a 40% drop in hypokalemia cases. No extra cost, no new meds-just better timing. Small changes, big impact.

matthew dendle

so u say dont stop diuretics but then u say add mras and sglt2i and potassium pills… so whats the point of the diuretic again? like is this just a 3000 word essay on how to patch a leaky boat while still dumping water out the hole? 🤔

Lisa Stringfellow

I read this whole thing and I’m just… tired. Why does every medical post have to feel like a lecture? Bananas aren’t enough? Okay. But do we really need 12 paragraphs explaining what a loop diuretic does? I’m not a nurse. I’m just someone trying to understand why my grandpa’s legs keep swelling. This is overwhelming.

Kristi Pope

Big love for the SGLT2i mention-these drugs are quiet heroes. I’ve had patients who thought they were just for diabetes, and then boom, their breathing improved and their potassium stayed cozy. It’s like the body finally got a break. And yes, potassium isn’t just about bananas-it’s about balance. Think of it like a symphony: diuretics play the drums, MRAs the strings, and SGLT2is? They’re the conductor making sure no one’s out of tune.

Sylvia Frenzel

Why are we treating heart failure like it’s a problem only Americans can solve? In Europe, they use lower doses, focus on diet, and don’t overload patients with pills. This post reads like a pharma pamphlet. Diuretics aren’t magic. Maybe we need fewer drugs and more lifestyle. Just saying.

john damon

Splitting the dose? 🤯 I’m gonna try this tonight. Also, if you’re not using SGLT2i yet… you’re basically using a flashlight in a blackout 😅