Imagine a hidden network that stretches across forests, farms, and even your kitchen counter-an organism that can turn dead wood into soil, brew your bread, and produce life‑saving medicines. That powerhouse is the fungusa kingdom of organisms distinct from plants, animals, and bacteria, thriving by breaking down organic matter or forming partnerships with other life forms. This introduction will pull back the veil on the strange, useful, and sometimes spooky world of fungi.

- Fungi form a separate biological kingdom with unique cell walls made of chitin.

- They fall into three main groups: mushrooms, yeasts, and molds.

- Mycelium is the living, thread‑like network that does most of the work.

- Ecologically, fungi recycle nutrients, partner with plants, and can cause disease.

- Humans harvest fungi for food, medicine, and industrial processes.

What Exactly Is a Fungus?

A fungusbelongs to the kingdom Fungi, characterized by cells surrounded by chitin, a fibrous polymer also found in insect exoskeletons. Unlike plants, fungi cannot photosynthesize; they obtain energy by absorbing dissolved nutrients from their environment. This mode of life lets them thrive in dark, damp places where plants would wither.

Major Groups: Mushrooms, Yeasts, and Molds

While the word “fungus” often brings images of toadstools, the kingdom is far broader.

Mushrooms are the fruiting bodies of certain fungi, much like apples are the fruit of an apple tree. They belong to the class Agaricomycetes and include familiar edibles such as the button mushroom, shiitake, and chanterelle.

Yeastare single‑cell fungi that reproduce primarily by budding and are essential in baking, brewing, and biofuel production-think of the fluffy dough rising in your oven.

Moldconsists of filamentous fungi that grow as a fuzzy coating on food, walls, or organic debris, reproducing via spores. Common household molds like Penicillium and Aspergillus are both friends (antibiotic producers) and foes (allergens).

Life Cycle: The Secret of Mycelium

At the heart of every fungus is myceliuma sprawling network of hyphae-thin, thread‑like filaments that explore and digest the substrate. When conditions are right, mycelium concentrates resources to spawn a fruiting body (the mushroom) or releases spores to colonize new territory.

Mycelial growth follows a few simple rules: hyphae extend at their tips, secrete enzymes to break down complex molecules, and absorb the resulting nutrients. This decentralized growth makes fungi incredibly resilient; a single mycelial mat can cover several acres and live for decades.

Ecological Superpowers

Fungi are the planet’s premier recyclers. By decomposing wood, leaf litter, and even hard keratin (think hair and nails), they return carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus to the soil, supporting plant life.

One of the most celebrated partnerships is mycorrhizaa symbiotic relationship where fungal hyphae exchange water and nutrients for sugars from plant roots. Over 80% of terrestrial plants rely on mycorrhizal fungi, which can increase tree growth by up to 30% in nutrient‑poor soils.

Not all fungi are helpers; some are pathogens. Phytophthora infestans caused the Irish potato famine, while Candida albicans can turn from a harmless gut resident into a dangerous infection when the host’s immune system weakens.

Human Uses: Food, Medicine, and Industry

Our relationship with fungi is ancient. Archaeological evidence shows humans gathering wild mushrooms over 10,000 years ago. Today, cultivated mushrooms generate a global market worth more than $50billion.

In the kitchen, mushrooms add umami, texture, and nutrition. The button mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) supplies B‑vitamins, selenium, and fiber, while exotic varieties like Lion’s Mane are touted for brain‑boosting compounds.

Medical breakthroughs owe much to fungi. penicillinthe first widely used antibiotic, was discovered in the mold Penicillium chrysogenum in 1928. Since then, fungi have yielded statins (cholesterol‑lowering drugs), immunosuppressants, and anticancer agents.

Industrial fermentation harnesses yeast to produce ethanol, bio‑plastic precursors, and high‑value enzymes. The rise of “mycelium‑based” packaging offers a biodegradable alternative to polystyrene.

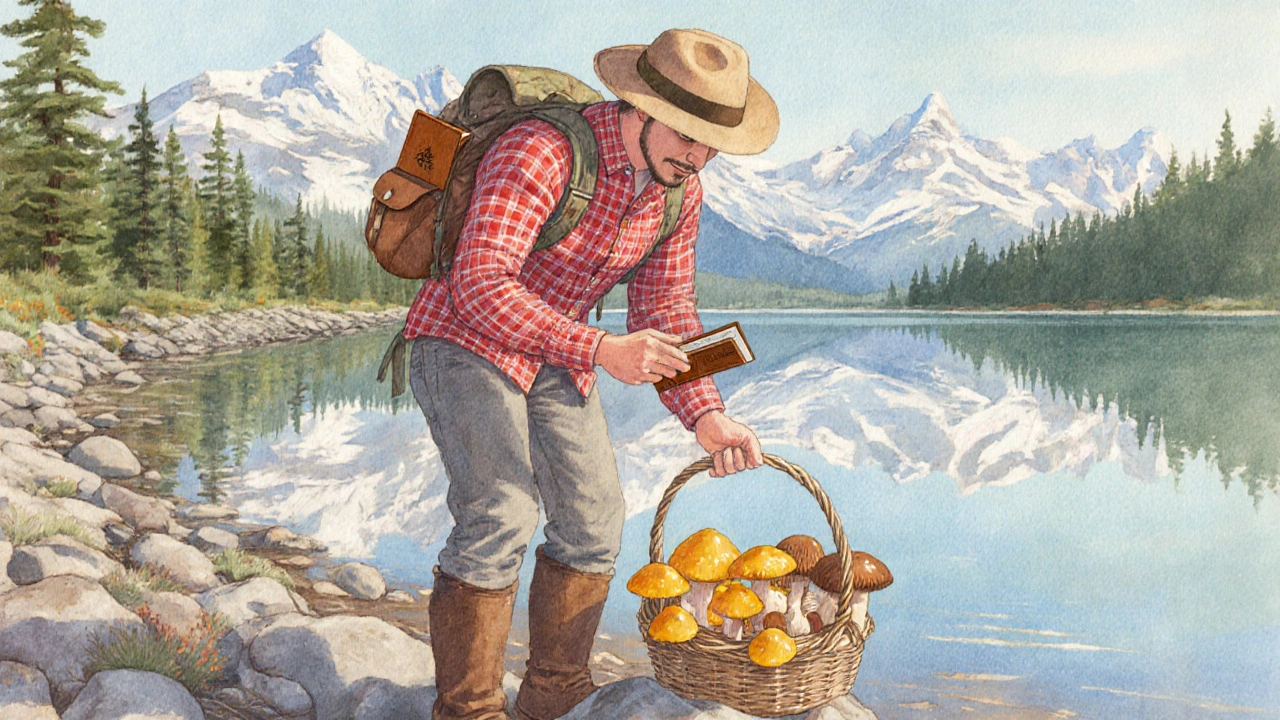

Getting Started: Safe Mushroom Hunting and Identification

If the idea of foraging mushrooms excites you, start with the basics. Always bring a reliable field guide or a smartphone app that cross‑references spore color, cap shape, and habitat. Never eat a mushroom unless you’re 100% certain of its identity; some species, like the death cap (Amanita phalloides), contain lethal toxins that can cause liver failure.

Key identification steps:

- Observe the habitat. Mycorrhizal mushrooms grow near specific trees; saprotrophic varieties appear on decaying wood.

- Check the cap and stem. Note size, color, texture, and any bruising reactions.

- Examine the gills or pores. Their attachment to the stem and color changes with age.

- Take a spore print. Place the cap gill‑side down on paper for several hours; the deposited spore color is a diagnostic clue.

- Smell it. Some edible mushrooms have pleasant almond or anise aromas, while poisonous ones may smell foul.

When in doubt, leave it. Most foragers adopt the rule: “If you can’t positively identify it, don’t consume it.”

Fun Facts & Myths About Fungi

- Fungi are more closely related to animals than to plants, sharing a common ancestor about 1.1billion years ago.

- The world’s largest organism is a honey‑comb fungus (Armillaria ostoyae) covering 3.4sqmi in Oregon.

- Bioluminescent fungi like *Mycena chlorophos* glow in the dark thanks to a chemical reaction similar to fireflies.

- “Mushroom coffee” and “fungi‑based nutraceuticals” are booming trends, driven by research into beta‑glucans and antioxidant compounds.

- Fungal networks can “talk” through electrical pulses, alerting neighboring trees to insect attacks-an early form of forest communication.

| Group | Typical Structure | Reproduction | Common Examples | Key Uses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mushrooms | Fruit body (cap, gills, stem) | Spore‑bearing on gills or pores | Button, shiitake, chanterelle | Food, medicinal extracts |

| Yeast | Single‑celled, oval | Budding, sexual asci in some species | Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Brettanomyces | Baking, brewing, bio‑ethanol |

| Mold | Filamentous hyphae forming a mat | Conidia (asexual spores) and sexual spores | Penicillium, Aspergillus, Rhizopus | Antibiotics, cheeses, biodegradation |

Quick Takeaways

Fungi are the unsung architects of ecosystems, the source of everyday foods, and the originators of life‑saving drugs. Whether you’re spotting a mushroom after a rainstorm, baking fresh bread, or reading about new fungal antibiotics, you’re witnessing a kingdom that has been reshaping our planet for millions of years.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are all mushrooms edible?

No. While many mushrooms are delicious, a significant number are poisonous. Proper identification is essential before consumption.

How does mycelium differ from a mushroom?

Mycelium is the vegetative network of threads that lives underground or within its substrate. The mushroom is just the reproductive fruiting body that emerges to release spores.

Can fungi help fight climate change?

Yes. Fungi sequester carbon in their mycelial mats and can be engineered to break down pollutants, making them valuable tools for carbon capture and environmental remediation.

What’s the difference between a mold and a fungus?

Mold is a type of fungus that grows as a fuzzy coating of hyphae. All molds are fungi, but not all fungi are molds.

How are antibiotics derived from fungi?

Molds like Penicillium produce secondary metabolites that inhibit bacterial growth. Scientists isolate, purify, and modify these compounds to create medicines like penicillin.

Jack Marsh

The assertion that fungi are universally beneficial overlooks the breadth of pathogenic species that threaten agriculture and human health. While mycorrhizal associations enhance nutrient uptake for many plants, they also create dependency that can be exploited by invasive fungi. Penicillin, a celebrated fungal derivative, represents a narrow fraction of the pharmacological potential hidden within the kingdom. Numerous molds produce potent mycotoxins that contaminate food supplies, leading to acute and chronic illnesses. The ecological dominance of certain saprotrophic fungi can suppress biodiversity by outcompeting slower-growing organisms. Moreover, the decomposition of woody debris by fungi releases carbon dioxide, contributing to greenhouse gas fluxes when not sequestered. The commercial exploitation of mushroom farming often relies on monoculture practices that diminish soil health. Genetic modification of fungal strains for industrial purposes raises biosecurity concerns that are insufficiently addressed. In forest ecosystems, the aggressive spread of Armillaria species can decimate trees and alter successional trajectories. Human reliance on fungal enzymes for biofuel production might inadvertently promote the evolution of resistant microbial communities. The romanticized image of mycelial networks as a form of forest internet ignores the competitive and antagonistic interactions that dominate underground. Bioinformatic analyses reveal that many fungal genomes contain cryptic gene clusters whose expression could be harmful if mobilized. Regulatory frameworks for novel fungal-derived compounds lag behind the rapid pace of discovery, leaving gaps in safety assessment. Consequently, a balanced perspective on fungi must acknowledge both their indispensable roles and their capacity for harm. An informed public discourse should therefore emphasize rigorous research rather than uncritical celebration.

Terry Lim

Fungal pathogens inflict billions of dollars in crop losses each year, and the literature often glosses over this impact. The rise of resistant strains such as Fusarium spp. underscores the need for vigilant management. Ignoring these facts does a disservice to agricultural sustainability.

Cayla Orahood

The hidden hands behind the mushroom boom are not just entrepreneurs, but shadowy biotech conglomerates steering research toward profit. They selectively highlight beneficial species while silencing studies on toxic metabolites that could jeopardize public health. Mycelial networks are touted as eco‑friendly, yet they can be weaponized to disseminate engineered genes across ecosystems. The “natural” label masks the fact that many fungal strains are genetically edited in secret labs. Consumers are fed a curated narrative that omits the environmental toll of large‑scale cultivation. Reports of air‑borne spores triggering allergic crises in urban centers are routinely downplayed. The pharmaceutical industry’s reliance on Penicillium derivatives also creates a monopoly that stifles alternative treatments. In short, the fungal renaissance may be as much about control as it is about curiosity.

McKenna Baldock

When we consider fungi as extensions of the forest mind, we recognize a symbiotic dialogue that transcends individual organisms. The mycelial web acts as a conduit for chemical signaling, subtly influencing plant behavior. This perspective invites us to reassess our anthropocentric view of nature. By embracing such humility, we may uncover more sustainable ways to coexist with these unseen allies.

Roger Wing

Fungi aren’t the miracle cure all hype claims they are they’re just another group of microbes with a few useful tricks but also a lot of hazards

Andy Williams

While Roger raises a valid point, his sentence suffers from missing punctuation; proper commas and periods are essential for clarity. Moreover, the claim that fungi are merely "another group of microbes" ignores their unique eukaryotic cell structure and ecological roles.

Paige Crippen

The concerns about undisclosed genetic modifications merit careful monitoring, yet many fungal applications undergo rigorous regulatory review. Balancing innovation with safety remains a central challenge.

sweta siddu

Fungi are truly fascinating! 🌱🍄 They’re everywhere from forest floors to our kitchens, turning simple ingredients into delicious breads and sauces. Exploring them can be a fun hobby, especially when you can spot the tiny glow of bioluminescent mushrooms on a night hike. Keep diving into the mushroom world, and you’ll keep discovering new marvels! 😊

Ted Mann

Sweta’s enthusiasm captures the essence of humanity’s age‑old curiosity toward the fungal kingdom, a curiosity that mirrors the quest for meaning itself. If we view mycelium as a living library, each hyphal thread writes a line in the grand narrative of Earth’s carbon cycle. This metaphor invites us to treat fungi not merely as tools but as teachers in the ecosystem’s classroom.

Brennan Loveless

While poetic analogies are appealing, they shouldn’t distract from the fact that much of the world’s food security depends on domesticated fungal species imported from Europe and Asia. Prioritizing native North American strains could reduce reliance on foreign supply chains and reinforce agricultural sovereignty.

Vani Prasanth

It’s encouraging to see the community sharing knowledge about safe foraging practices; mentoring newcomers helps preserve both traditions and biodiversity. Remember to always cross‑check spore prints and to respect local regulations when collecting.

Maggie Hewitt

Oh sure, because the biggest threat to humanity is definitely lacking the perfect mushroom identification guide, not climate change or pandemics. But hey, at least we’ll all look smart holding a spore‑print in a coffee shop.

Mike Brindisi

Actually mushroom IDs are based on macroscopic traits and microscopic spores no need for drama the key is consistency in observation and documentation

Steven Waller

Let’s foster an environment where both seasoned mycologists and curious beginners feel welcomed to ask questions and share discoveries; mentorship bridges gaps in knowledge and builds a resilient community.

Jay Ram

Sounds like a solid plan for everyone.

Elizabeth Nicole

I’m excited to see new collaborations sprouting, especially when they bring fresh perspectives to fungal research and sustainable applications.

Dany Devos

The article oversimplifies complex mycological concepts, presenting nuanced interactions as mere bullet points, which may mislead readers unfamiliar with the subject.

Sam Matache

Honestly, the whole “fungi are the unsung heroes” vibe feels a bit overhyped-there’s a lot more drama underground than anyone admits.