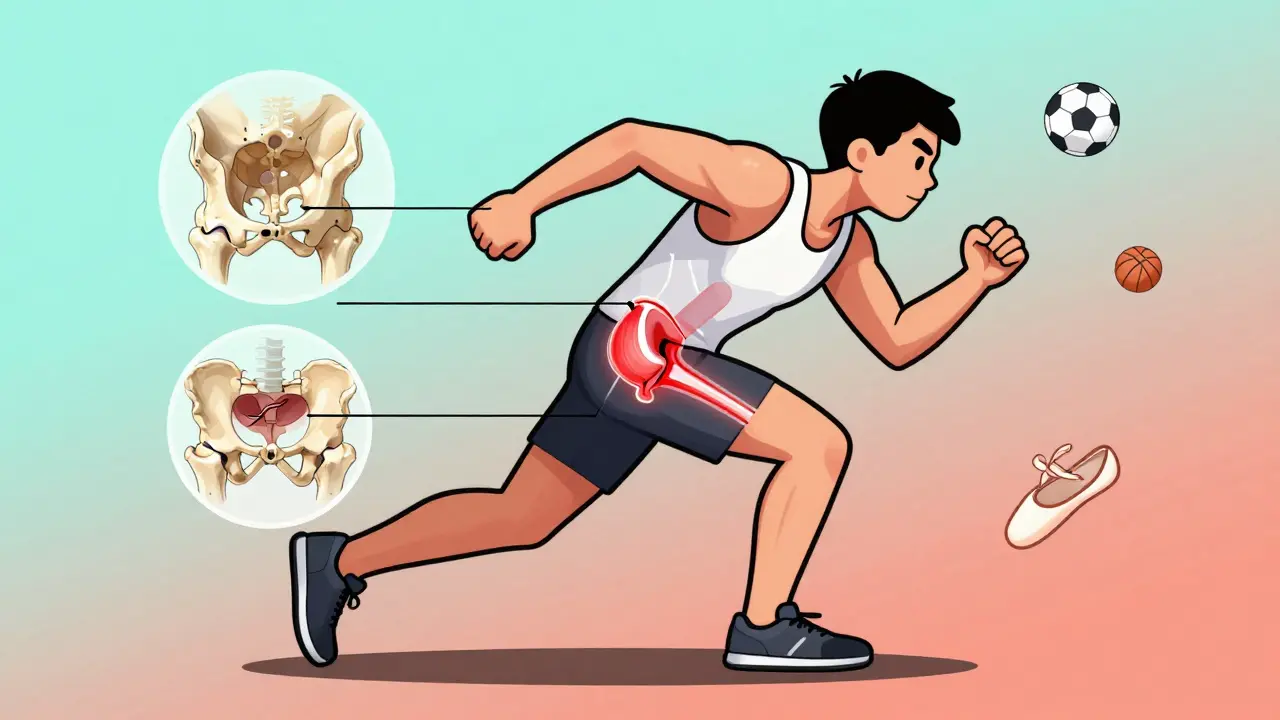

When an athlete feels a deep, sharp pain in the hip during a sprint, a kick, or a sudden twist, it’s rarely just a muscle strain. More often than not, it’s a hip labral tear - a problem that doesn’t show up on regular X-rays but can end seasons if ignored. The labrum is a ring of cartilage that wraps around the hip socket, acting like a gasket to keep the ball of the femur securely in place. When it tears, it doesn’t just hurt - it destabilizes the joint, increases friction, and sets the stage for early arthritis. For athletes under 40, especially those in soccer, basketball, hockey, or ballet, this isn’t a rare injury. It’s one of the most common causes of chronic hip pain in competitive sports today.

What Causes a Hip Labral Tear?

Most hip labral tears aren’t caused by a single traumatic event. They develop over time. The biggest culprit? Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI). This means the bones of the hip joint don’t fit together perfectly. One bone - either the femoral head or the acetabulum - has an extra bump or is too shallow. Every time the athlete moves, that abnormal bone grinds against the labrum, slowly wearing it down. Think of it like a misaligned door hinge: the more you open and close it, the more the edge frays. Sports that involve repetitive hip rotation - soccer tackles, basketball pivots, hockey stops, ballet pliés - put the most stress on this area. A 2022 study found that basketball players make up 22% of all diagnosed cases, soccer 18%, and hockey 15%. Even runners aren’t safe; 12% of labral tears occur in marathoners. And it’s not just about how much you train. Some people are born with a hip shape that makes them more vulnerable. Hip dysplasia - where the socket is too shallow - increases the risk of re-tearing after surgery by 60-70% if not corrected.How Do Doctors Diagnose It?

You can’t just rely on how it feels. Many athletes have pain but no tear. Others have a visible tear on imaging but no symptoms. That’s why diagnosis needs to be precise. The first step? Plain X-rays. Not to see the tear - it won’t show up - but to check for bone abnormalities. Doctors look for FAI, hip dysplasia, or signs of early arthritis. They take multiple views: front, side, frog-leg, and false profile. If the bones look off, the next step is imaging the soft tissue. Standard MRI misses about 30% of labral tears. That’s why magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) is now the gold standard. In MRA, a contrast dye is injected into the hip joint before the scan. The dye seeps into any tear, making it glow clearly on the image. Studies show MRA detects labral tears with 90-95% accuracy. It’s not cheap - $1,200 to $1,800 out-of-pocket - but for athletes, it’s worth it. Without it, you might be treated for a strain when you actually need surgery. Physical exams help too. The FADIR test (flexion, adduction, internal rotation) and FABER test (flexion, abduction, external rotation) are done in the clinic. If these movements cause sharp pain or a clicking sensation, there’s a 78% chance a labral tear is present. But these tests alone aren’t enough. They point to the problem. MRA confirms it.What Happens During Arthroscopy?

If conservative treatments fail - rest, NSAIDs, physical therapy - and the tear is confirmed, arthroscopy is the next step. It’s not open surgery. Surgeons make two or three tiny incisions around the hip. A small camera (arthroscope) goes in, and with it, miniature tools. There are two main approaches: debridement and repair. Debridement means trimming away the torn, frayed part of the labrum. It’s faster, with a 3-4 month recovery. But it’s not always the best choice. If the labrum is still mostly intact, cutting it out removes the joint’s natural cushion. That increases long-term risk of arthritis. Repair is more involved. Surgeons use tiny suture anchors - small devices that look like screws with thread - to stitch the torn labrum back onto the bone. This restores the joint’s seal. It’s the preferred method for younger athletes with good tissue quality. Recovery takes 5-6 months. The key? The anchor must hold. That’s why new bioabsorbable anchors, approved by the FDA in June 2023, are changing outcomes. Made from materials that dissolve over time, they reduce long-term complications and have shown 89% success at two years.

Recovery and Return to Sport

Recovery isn’t just about waiting for the pain to go away. It’s about rebuilding strength, control, and movement patterns. A typical rehab plan has four phases:- Protection (weeks 1-6): No weight-bearing on the hip. Use crutches. Avoid internal rotation. Focus on gentle motion to prevent stiffness.

- Strengthening (weeks 7-12): Start working on glutes, quads, and core. Balance exercises begin. No running or jumping.

- Sport-specific training (weeks 13-20): Gradual return to sport movements. Agility drills, controlled pivots, light cutting.

- Full return (weeks 21-26): Only when quadriceps strength matches the uninjured side by 90% and hip internal rotation reaches 30 degrees pain-free.

Why Some Treatments Fail

Not everyone gets better. About 15-20% of patients still have pain after surgery. Why? One big reason: untreated underlying issues. If you have hip dysplasia and only repair the labrum, the joint stays unstable. Studies show 65% of those cases re-tear within two years. That’s why top centers now combine labral repair with osteotomy - a procedure to reshape the socket. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons warns against isolated debridement. It increases revision rates by 40%. Another issue? Surgeon experience. Hip arthroscopy has a steep learning curve. Surgeons need 50-100 procedures to become competent. Athletes treated at specialized sports medicine centers report 92% satisfaction. At general orthopedic clinics? Only 75%.

What’s New in 2026?

The field is evolving fast. In 2023, 3D MRI sequencing became a recommended tool for complex cases. It gives surgeons a 360-degree view of the labrum and bone shape, improving diagnosis to 97%. Regenerative treatments like PRP (platelet-rich plasma) injections are being tested. One trial showed 55% of patients avoided surgery entirely after one injection. It’s not a cure, but it might delay it. The market is booming. Over 150,000 hip arthroscopies were done in the U.S. in 2022 - triple the number from 2010. The global market hit $1.2 billion. But the goal isn’t just more surgeries. It’s smarter ones. The future lies in early detection, personalized repair techniques, and preventing osteoarthritis before it starts.When to Seek Help

If you’re an athlete and have:- Deep hip pain that doesn’t improve with rest

- Pain during or after rotation, squatting, or sitting for long periods

- A clicking or locking sensation in the hip

- History of hip dysplasia or FAI

Can a hip labral tear heal without surgery?

In some cases, yes - but not always. Conservative treatment with rest, NSAIDs, and physical therapy helps about 30-65% of athletes, depending on tear severity and underlying anatomy. If the tear is small, not degenerative, and there’s no hip dysplasia, non-surgical options can work. But if the labrum is torn and unstable, or if FAI or dysplasia is present, the tear will likely worsen. Surgery is often needed to prevent early arthritis.

Is MRA better than regular MRI for hip labral tears?

Yes, significantly. Standard MRI detects labral tears with only 35-60% accuracy. MRA, which uses contrast dye injected into the joint, improves accuracy to 90-95%. It’s especially good at spotting partial tears and distinguishing between degeneration and true injury. For athletes considering surgery, MRA is the standard of care.

How long does recovery take after hip arthroscopy?

It depends on the procedure. If the torn labrum is trimmed (debridement), recovery is typically 3-4 months. If the labrum is stitched back (repair), recovery takes 5-6 months. Full return to high-level sports requires meeting specific strength and mobility benchmarks - not just time. Most athletes can’t return before 20 weeks.

Why do some athletes need revision surgery?

The most common reason is untreated underlying hip anatomy problems - like dysplasia or FAI. If the bone structure isn’t corrected, the repaired labrum is under constant stress and re-tears. Surgeon inexperience, poor rehab, and rushing return to sport also increase revision risk. Revision rates are 8-12% at five years.

Can hip labral tears lead to arthritis?

Yes. The labrum acts as a cushion and seal for the hip joint. When it’s torn, the ball and socket rub directly on bone, increasing wear. Studies show untreated labral tears raise the risk of osteoarthritis by 4.5 times within 10 years. Early diagnosis and proper treatment - especially correcting bone abnormalities - can significantly delay or prevent this.

Ed Mackey

man i just got back from PT for my hip and they said the same thing about MRA vs regular MRI. i got the regular one first and it was like 'maybe a strain?' then i paid for the MRA and boom-full tear. worth every penny if you’re serious about playing again.

caroline hernandez

debridement vs repair is such a critical decision point. if you're under 30 and active, repair is the only way to go-debridement is basically gambling with your joint longevity. i've seen too many athletes come back with worse pain 2 years later because they took the 'faster recovery' route. glute medius activation in phase 2? non-negotiable.

Sherman Lee

they’re hiding the truth. the real reason hip arthroscopy is booming? insurance companies push it because it’s cheaper than lifelong pain meds. and those ‘bioabsorbable anchors’? patented by big pharma to keep you coming back for ‘follow-ups’. 92% satisfaction? sure… if you ignore the 30% who still can’t squat without screaming.

Antwonette Robinson

oh wow, so the 'gold standard' is injecting dye into your hip? genius. next they’ll be teaching cats to do MRI scans. at least my dog gets a treat after vet visits. i get a $1,500 bill and a pamphlet on 'rehab compliance'. thanks, medicine.

Coy Huffman

it’s wild how we treat the body like a machine you can just swap parts out. the labrum isn’t a gasket-it’s a sensory organ. when you cut or stitch it, you’re messing with proprioception too. maybe the real solution isn’t surgery at all… but retraining how we move from day one. why do we wait until the joint screams before we listen?

Alex LaVey

to anyone reading this and thinking 'i can just tough it out'-please don’t. i was a college soccer player, ignored the pain for 8 months, and ended up with early arthritis at 28. getting the MRA was the best decision i ever made. it’s not just about playing again-it’s about walking without pain at 50. you owe it to your future self.

Daz Leonheart

recovery phase 3 is where most people fail. they think 'i’m not in pain anymore' means they’re ready. nah. you need control, not just motion. i did 3 months of single-leg balance drills on a foam pad before i even touched a ball again. no shortcuts. your hip will remember.

Jesse Naidoo

you guys are all missing the point. why is this happening so much now? because we’re all sitting on our asses 8 hours a day then exploding into sport. our hips are frozen, then forced into rotation. fix the sitting, not the surgery. also, who approved those anchors? i bet they’re made in China.