When a patient switches from a brand-name extended-release pill to a generic version, they expect the same effect-same control of blood pressure, same pain relief, same steady mood. But with modified-release formulations, that’s not always guaranteed. Unlike immediate-release drugs that dump their entire dose at once, modified-release (MR) products are engineered to release medication slowly, in phases, or at specific locations in the gut. This complexity makes proving they work the same as the original drug far harder than it sounds. And if you’re a pharmacist, clinician, or even a patient wondering why a generic isn’t working the same way, the answer often lies in how bioequivalence was tested-and whether the right tests were even done.

Why Modified-Release Formulations Are Trickier Than They Look

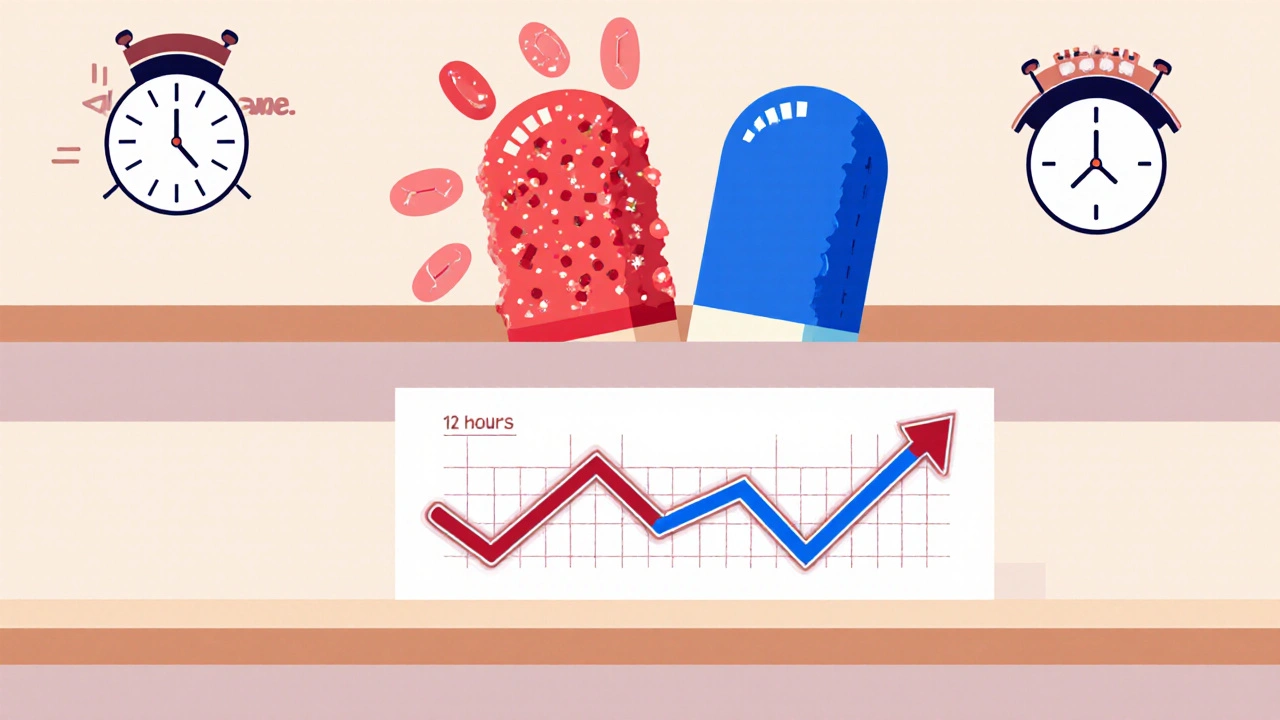

Imagine two pills: one releases all its medicine in 30 minutes, the other spreads it out over 12 hours. Both have the same total amount of drug. But if the slow-release pill releases too fast at first, you get a spike in blood levels-maybe even side effects. If it releases too slowly, you don’t get enough drug when you need it. That’s why bioequivalence for these products isn’t just about total exposure (AUC). You have to look at when and how fast the drug shows up.

Take a drug like methylphenidate ER (Concerta). It’s designed to have two peaks: one early (for quick symptom control) and one later (to last through the day). If a generic version doesn’t match both peaks exactly, even if the total AUC is perfect, patients can experience breakthrough symptoms or rebound effects. That’s why the FDA rejected a generic version of Concerta in 2012-not because it was unsafe, but because it didn’t replicate the early release phase. The test failed to measure partial AUC from 0 to 2 hours, a critical window.

That’s not an isolated case. Between 2018 and 2021, 22% of generic MR applications were initially turned down by the FDA because they didn’t properly assess these time-specific release patterns. Most people assume bioequivalence is just about matching AUC and Cmax. For MR drugs, that’s only half the story.

How Regulators Test Bioequivalence for Modified-Release Drugs

There’s no single global standard. The FDA, EMA, and WHO all have different rules-and they often contradict each other.

The FDA’s 2022 guidance is the strictest. For extended-release (ER) tablets, they require:

- Single-dose, fasting studies (not multiple doses)

- Measurement of partial AUC (pAUC) at clinically relevant timepoints-for example, 0-1.5 hours and 1.5 hours to infinity for zolpidem CR

- Dissolution testing at three pH levels: 1.2 (stomach), 4.5 (upper intestine), and 6.8 (lower intestine)

- Alcohol interaction testing for any ER product with 250 mg or more of active ingredient

Why alcohol? Because some ER tablets can suddenly release their entire dose if taken with alcohol-a phenomenon called “dose dumping.” Between 2005 and 2015, seven ER opioid products were pulled from the market after reports of fatal overdoses linked to alcohol consumption. The FDA now requires this test for over 120 products.

The EMA takes a different approach. They still require steady-state studies (multiple doses over days) for some MR products, especially if the drug accumulates in the body. They also focus on metrics like half-value duration (HVD) and midpoint duration time (MDT), which measure how long the drug stays in the therapeutic range-not just how much is absorbed.

And then there’s the WHO, which claims MR bioequivalence criteria are “essentially the same” as for regular drugs. But that’s not what manufacturers or regulators see in practice. In fact, most MR generics approved in the U.S. or Europe would fail under WHO’s looser standards.

What Happens When the Tests Don’t Match

Here’s the uncomfortable truth: some generic MR drugs meet regulatory bioequivalence standards-and still cause problems in real patients.

A 2016 study in Neurology found that 18% of generic extended-release antiepileptic drugs showed higher seizure breakthrough rates than the brand version-even though they passed all standard bioequivalence tests. Why? Because the release profile was slightly off. Maybe the drug peaked 30 minutes later. Maybe it didn’t sustain long enough. These tiny shifts don’t show up in AUC or Cmax-but they matter in the clinic.

One formulation scientist at Teva told the American Pharmaceutical Review that 35-40% of early attempts to develop generic ER oxycodone failed because they couldn’t match dissolution profiles across all three pH levels. The drug behaved differently in stomach acid than in the intestine. It wasn’t a manufacturing flaw-it was a formulation design flaw.

And then there’s the cost. Developing a generic MR drug costs $5-7 million more than a regular one. A single-dose bioequivalence study for an ER product runs $1.2-1.8 million, compared to $800,000-$1.2 million for immediate-release. That’s why only large pharma companies and big generic manufacturers (like Teva, Sandoz, Mylan) can afford to play. Small biotechs? They rarely even try.

Special Cases: High Variability and Narrow Therapeutic Index Drugs

Some drugs are naturally unpredictable in the body. Warfarin, lithium, and certain antiepileptics have a narrow therapeutic index-meaning the difference between a therapeutic dose and a toxic one is tiny. For these, the FDA requires tighter bioequivalence limits: 90.00-111.11% instead of the standard 80-125%.

And then there are highly variable drugs-where the same person’s blood levels can swing wildly from day to day. For these, the FDA uses a method called Reference-Scaled Average Bioequivalence (RSABE). It allows wider acceptance limits, but only if the reference product itself is highly variable. The catch? RSABE adds 6-8 months to development time because the statistical models are complex, and you need more subjects to get reliable data.

One clinical pharmacologist at Mylan said on LinkedIn that implementing RSABE for a modified-release version of a highly variable drug nearly doubled their study timeline. “It’s not just running more samples,” they wrote. “It’s rethinking your whole analysis plan.”

What You Need to Know as a Patient or Provider

So what does this mean for you?

If you’re on an extended-release medication-especially for conditions like ADHD, epilepsy, hypertension, or chronic pain-and you switch to a generic version, pay attention. Do you notice changes in how you feel? More side effects? Less control? Don’t assume it’s just your imagination. It could be a subtle difference in release timing.

Ask your pharmacist: “Is this generic been tested for modified-release bioequivalence?” If they look confused, it’s a red flag. Not all generics are created equal, and the ones that skip the extra testing (like pAUC or alcohol testing) may not be as reliable.

And if you’re switching back and forth between brands and generics? Keep a journal. Note when symptoms change, when side effects appear, or when you feel “off.” That data can help your doctor decide whether to stick with one version.

The Future: Better Tools, Fewer Surprises

The good news? The industry is catching up. The FDA is working on a new 2024 guidance for complex MR products-things like gastroretentive systems and multiparticulate beads. They’re also accepting in vitro-in vivo correlation (IVIVC) models more often. That means if a drug’s release pattern in a test tube perfectly predicts how it behaves in the body, you might not need a human study at all.

Companies like Janssen have already used IVIVC to get approval for extended-release paliperidone without a full bioequivalence trial. That saves millions and speeds up access.

Meanwhile, physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling is becoming standard in big pharma. These computer simulations predict how a drug will behave based on anatomy, physiology, and chemistry-reducing guesswork. According to a 2022 DIA survey, 68% of major pharmaceutical companies now use PBPK for MR development.

But until these tools become routine for generics, the gap between regulatory approval and real-world performance will remain. The science is there. The tools exist. But the cost, complexity, and regulatory patchwork mean many generics still slip through with incomplete testing.

Modified-release formulations are here to stay. By 2028, IQVIA predicts they’ll make up 42% of all prescription sales. As aging populations need more chronic disease management, these drugs will become even more common. But if we don’t demand better bioequivalence testing, we’ll keep seeing cases where patients pay less for a generic-and pay more in side effects, hospital visits, or lost control of their condition.

Are all generic modified-release drugs the same as the brand?

No. While all generics must meet regulatory bioequivalence standards, the tests for modified-release (MR) drugs are more complex than for immediate-release products. Some generics pass the basic AUC and Cmax tests but fail to replicate the exact timing of drug release-especially in multiphasic or extended-release formulations. This can lead to differences in effectiveness or side effects in real-world use, even if the drug is technically "bioequivalent."

Why does alcohol matter with extended-release pills?

Alcohol can cause "dose dumping"-a sudden, uncontrolled release of the entire drug dose. This is especially dangerous with opioids, stimulants, or other drugs with narrow therapeutic windows. The FDA now requires alcohol interaction testing for any ER product containing 250 mg or more of active ingredient. Between 2005 and 2015, seven ER drugs were withdrawn after reports of fatal overdoses linked to alcohol consumption.

What is pAUC and why is it important?

pAUC stands for partial area under the curve. It measures drug exposure over a specific time window, not the entire duration. For drugs with multiple release phases-like zolpidem CR or methylphenidate ER-pAUC helps determine if the early and late release components match the brand. Missing this step is why some generics were rejected by the FDA, even when total AUC looked fine.

Why do some generics cause more side effects?

Even small differences in release timing can cause side effects. For example, if a generic releases too quickly, it can cause a spike in blood levels leading to dizziness or nausea. If it releases too slowly, you may not get enough drug at the right time, leading to breakthrough symptoms. These differences often don’t show up in standard bioequivalence tests but can be very real to patients.

How can I tell if my generic is a high-quality MR product?

There’s no public database listing which generics passed advanced testing. But if you notice changes in how you feel after switching-like increased side effects, reduced effectiveness, or new symptoms-talk to your doctor. Ask your pharmacist if the generic was tested for pAUC, alcohol interaction, or multi-pH dissolution. If they can’t answer, it may be worth sticking with the brand or asking for a different generic.

Shirou Spade

It's wild how we treat pills like they're magic bullets, but the release profile is basically the soul of the drug. You can have the same amount of medicine, but if it hits your system like a sledgehammer instead of a slow tide, you're not getting the same experience. It's not just chemistry-it's timing, rhythm, the whole damn ballet of absorption. And yet we let generics slide if they hit the AUC numbers? That's like judging a symphony by total notes played, not when they're played.

Who decides what 'clinically relevant' means anyway? Is it the FDA, or the patient who wakes up at 3 AM with a pounding headache because the 8 AM dose didn't kick in until noon? The math doesn't lie, but the body does. And the body doesn't care about regulatory loopholes.

Lisa Odence

As a board-certified clinical pharmacologist with 22 years of experience in therapeutic drug monitoring and bioequivalence protocol design, I must emphasize that the FDA’s 2022 guidance on modified-release formulations represents the gold standard-period. The EMA’s reliance on steady-state pharmacokinetics and WHO’s outdated, one-size-fits-all approach are scientifically indefensible. The pAUC metric is non-negotiable for multiphasic drugs like Concerta or zolpidem CR, and the alcohol challenge test is not optional-it’s a lifesaving requirement. Any generic that bypasses these is not bioequivalent; it’s a pharmacological gamble. Patients deserve better than regulatory arbitrage disguised as cost savings. 🚨💊📉

Patricia McElhinney

OMG this is why generics are dangerous!! I’ve been saying this for YEARS!! The FDA doesn’t even test for the right things and then they approve these cheap knockoffs and people die!! I read a study where a guy took a generic oxycodone ER and it dumped all at once because the pH didn’t match and he OD’d!! And now they want to use computer models instead of REAL HUMAN TRIALS?? That’s just lazy science!! The WHO is a joke and if you’re taking a generic for anything with a narrow therapeutic window you’re basically playing Russian roulette with your life!! 🤬⚠️

Dolapo Eniola

Man, this whole thing is a scam cooked up by Big Pharma and FDA to keep Africans and Indians from getting affordable meds!! You think we don’t know? They make the testing so complicated, so expensive, so full of pH levels and alcohol tests-just to protect the brand names!! We’ve been using generics for decades in Nigeria and India and people are fine!! Why do they need all this fancy math? Why not just trust the dose? It’s the same pill!! You think we can afford $1.8 million studies? Nah, we need medicine, not PhD theses!! 🇳🇬💊 #StopPharmaColonialism

Agastya Shukla

Interesting how the industry’s technical complexity is being framed as a failure of regulation, but the real issue is systemic underinvestment in bioequivalence infrastructure outside the U.S. and EU. The pAUC, MDT, and IVIVC frameworks aren’t just regulatory hurdles-they’re scientific necessities for drugs with nonlinear kinetics. But if you’re a generic manufacturer in a low-resource setting, you don’t have access to the dissolution apparatuses, the physiologically based modeling software, or the clinical trial networks to even attempt compliance. It’s not that the standards are wrong-it’s that the global equity gap in pharmaceutical R&D infrastructure is widening. We need open-source PK modeling tools and shared bioequivalence data repositories-not just stricter rules.

Pallab Dasgupta

YOOOO I just switched my son’s Adderall XR to a generic last month and he’s been zonked out by 2 PM and then bouncing off the walls at 10 PM-like what even is this?? I thought generics were supposed to be the same?? Now I’m reading this and it makes TOTAL sense!! The timing’s off, the peaks are wrong, and nobody told us!! I’m switching back to brand, even if it costs me my rent this month. This isn’t about money-it’s about my kid’s focus, his sleep, his sanity!! 😭💊 #GenericFail #ADHDParentsUnite

Ellen Sales

It’s not just about the science-it’s about trust. When a patient takes a pill, they’re not just ingesting molecules, they’re placing faith in a system. And when that system allows a drug to pass regulatory muster but still causes breakthrough seizures or sudden opioid spikes? That trust shatters. And rebuilding it? That takes years. And a whole lot of stories like this one. So yes, the math matters. The pH matters. The alcohol test matters. But what matters more? Listening to the people who live with these drugs every day. Not just the regulators. Not just the labs. The patients. The ones who notice the difference before the data does. 💙