Neonatal Medication Risk Calculator

This tool helps determine if medications like sulfonamides are safe to administer to a jaundiced newborn based on key clinical factors. Follow the AAP guidelines for preventing kernicterus.

Phototherapy Threshold Reference: Based on AAP guidelines

For age < 24 hours: < 5 mg/dL

For age 24-48 hours: < 7 mg/dL

For age 48-72 hours: < 9 mg/dL

For age > 72 hours: < 10 mg/dL

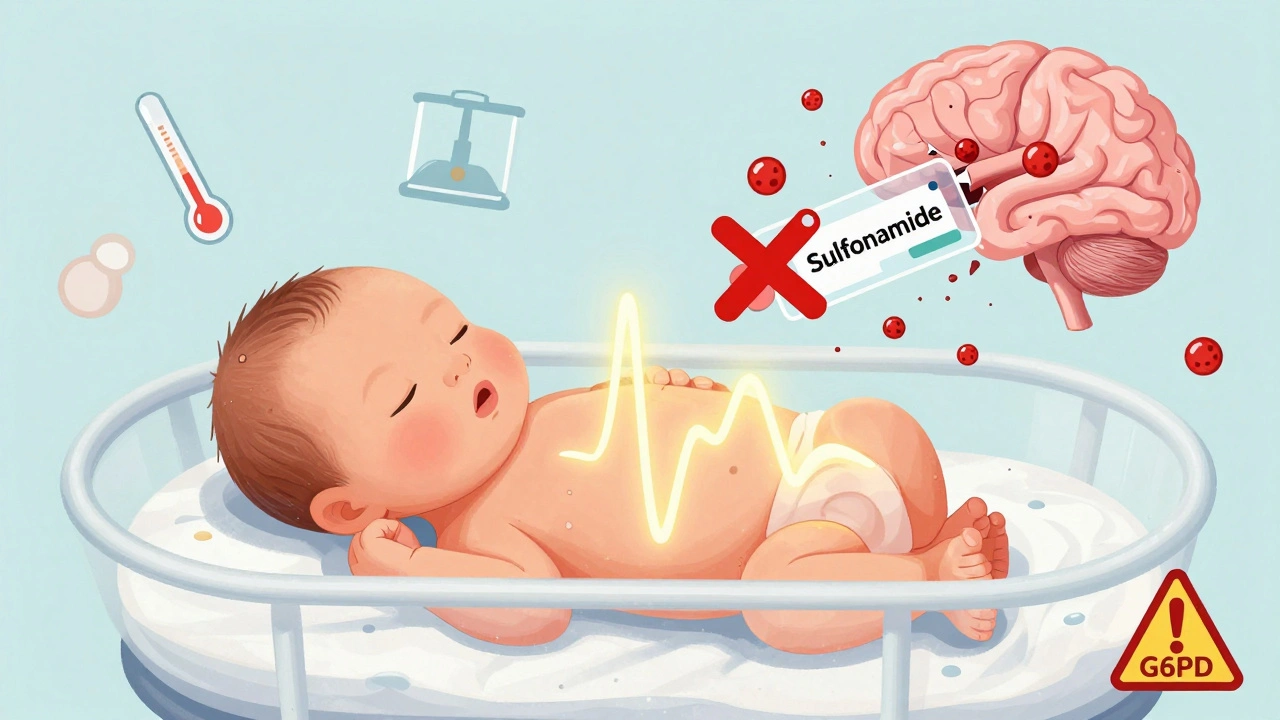

Neonatal kernicterus is a devastating but preventable brain injury caused by too much bilirubin in a newborn’s blood. It doesn’t happen because a baby is jaundiced-it happens when that jaundice isn’t managed properly, and certain medications push bilirubin into the brain. Even today, in 2025, this condition still occurs. And in nearly every case, it’s linked to something avoidable: the wrong drug given at the wrong time.

What Is Kernicterus, Really?

Kernicterus isn’t just severe jaundice. It’s when unconjugated bilirubin, a yellow pigment made when red blood cells break down, crosses the blood-brain barrier in a newborn and stains parts of the brain-especially the basal ganglia. This isn’t a theory. It’s visible under a microscope. Babies who survive often have lifelong problems: hearing loss, cerebral palsy, intellectual disabilities, or gaze abnormalities. The damage is permanent. And according to a 2019 study of nearly a million Swedish infants, it happens in about 1.3 out of every 100,000 term and near-term births. That sounds rare-but it’s not random. It’s preventable.Why Sulfonamides Are Dangerous for Newborns

Sulfonamides, like sulfisoxazole and sulfamethoxazole, were once common antibiotics for newborns. Now, they’re a red flag. These drugs compete with bilirubin for binding sites on albumin, the protein that normally carries bilirubin safely through the bloodstream. When sulfonamides displace bilirubin, free bilirubin levels spike. In a newborn, whose blood-brain barrier is still developing, that free bilirubin slips into the brain. Studies show sulfonamides can displace 25-30% of bilirubin from albumin at standard doses. That’s not a small effect. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) explicitly lists sulfonamides as high-risk drugs in their 2022 guidelines. Even a single dose in a baby with bilirubin levels near the phototherapy threshold can trigger a dangerous surge. One NICU nurse in Texas reported a 5-day-old infant’s bilirubin jumped from 14.2 mg/dL to 22.7 mg/dL within 12 hours after receiving sulfisoxazole for a urinary tract infection. That baby needed emergency phototherapy and nearly required an exchange transfusion.Other Medications That Put Newborns at Risk

Sulfonamides aren’t the only offenders. Ceftriaxone, a common IV antibiotic, displaces 15-20% of bilirubin. Aspirin and other salicylates do the same. Even furosemide, a diuretic sometimes used for fluid overload, can increase free bilirubin. These drugs don’t cause jaundice-they make existing jaundice far more dangerous. The risk isn’t just about the drug. It’s about timing and context. A baby with low albumin (below 3.0 g/dL), acidosis, or G6PD deficiency is at exponentially higher risk. G6PD deficiency affects about 7% of the global population and causes red blood cells to break down faster, flooding the system with bilirubin. Giving sulfonamides to a G6PD-deficient newborn is like pouring gasoline on a fire.

How Risk Is Measured and Managed

There’s no single number that says “safe” or “dangerous.” But clinicians use tools to assess risk. The free bilirubin index-measuring unbound bilirubin-is the gold standard. Levels above 10 mcg/dL are considered dangerous. But not every hospital can test for it. That’s why the AAP recommends a simpler approach: if a baby’s total serum bilirubin is above 75% of the phototherapy threshold for their age in hours, avoid sulfonamides and other displacing drugs entirely. Albumin levels matter too. If albumin is low, even normal bilirubin levels become risky. In preterm babies or those with infection, the binding capacity drops even more. The rule of thumb: for every gram of albumin, you can safely bind 0.5-1.0 mg of bilirubin. If albumin is 2.5 g/dL, you’re only safe up to about 2.5 mg/dL of bilirubin. Anything above that needs urgent attention-and no sulfonamides.What Should Doctors and Nurses Do?

The AAP’s 5-step checklist is clear:- Check the infant’s bilirubin level. If it’s above 75% of the phototherapy threshold, don’t use sulfonamides or ceftriaxone.

- Check albumin. If it’s below 3.0 g/dL, avoid all bilirubin-displacing drugs.

- Screen for G6PD deficiency if the baby is from a high-risk population (Mediterranean, African, Southeast Asian descent).

- If possible, calculate the free bilirubin index.

- Choose safer alternatives-like amoxicillin-clavulanate-when treating infections.

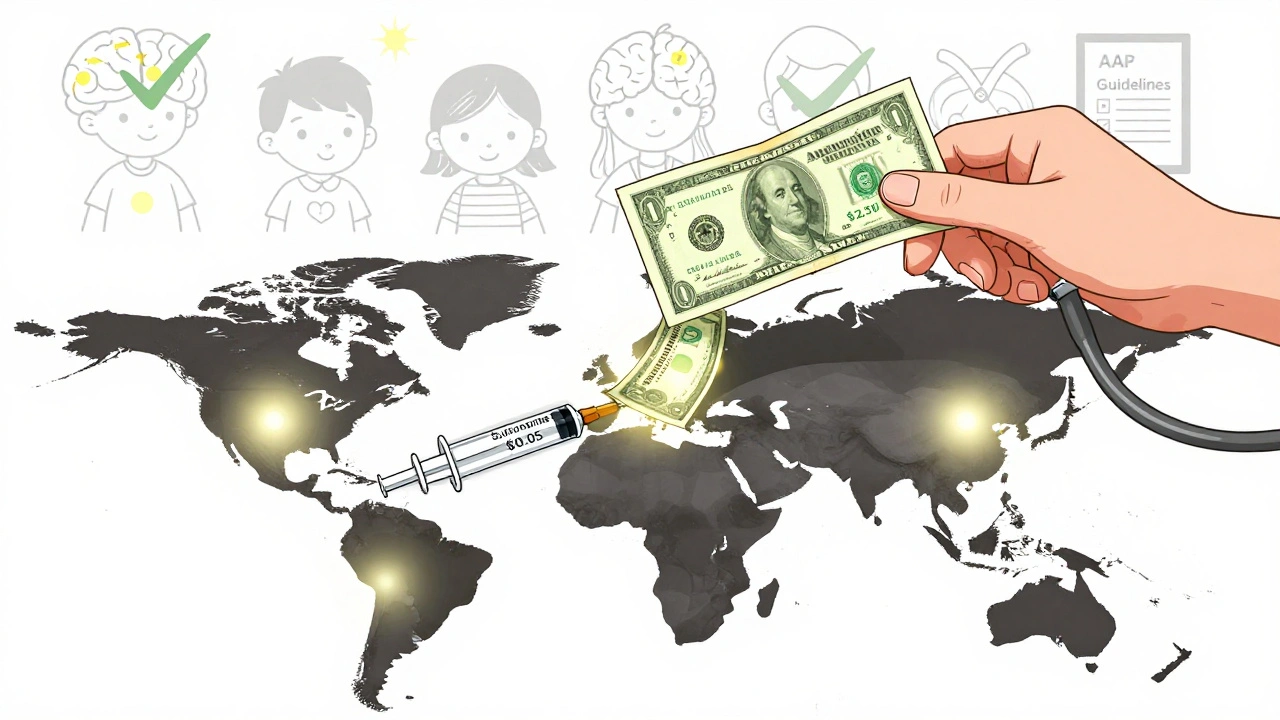

Why Are These Drugs Still Being Used?

You’d think this would be settled. But in resource-limited settings, sulfonamides are still used because they cost about $0.05 per dose. Amoxicillin-clavulanate costs $2.50. In places without robust newborn screening, the temptation to use cheap, accessible drugs is strong. That’s where preventable tragedies still happen. Even in the U.S., a 2022 review of malpractice cases found that 12% of kernicterus lawsuits involved inappropriate sulfonamide use. The average payout? $4.2 million. That’s not just a medical error. It’s a systemic failure.

Technology Is Helping-But Not Everywhere

Hospitals with electronic health records (EHRs) are starting to catch these mistakes before they happen. Epic Systems added automatic alerts in late 2023 that block sulfonamide orders if the newborn’s bilirubin is too high. That’s a big step. But only 78% of U.S. hospitals have adopted any kind of medication safety protocol, and rural hospitals are far behind. About 23% of rural U.S. hospitals still don’t have rapid bilirubin testing. That means decisions are made on guesswork. The NIH is funding new point-of-care devices to measure free bilirubin quickly and cheaply. If those succeed, we could see a major drop in preventable cases-even in low-resource areas.What Parents Should Know

Most parents won’t hear the word “kernicterus” until it’s too late. But they can ask questions:- Is my baby’s bilirubin level being monitored regularly?

- Are you checking albumin levels if the jaundice is severe?

- What antibiotic are you prescribing? Is it safe for newborns with jaundice?

- Has my baby been screened for G6PD deficiency?

The Bottom Line

Kernicterus is a silent threat. It doesn’t announce itself with screaming or seizures until it’s too late. The only way to stop it is to stop the wrong drugs from being given. Sulfonamides have no place in newborn care when bilirubin levels are elevated. Ceftriaxone, aspirin, and furosemide need careful review too. Safer alternatives exist. Protocols exist. Technology exists. The real question isn’t whether we know how to prevent kernicterus. It’s whether we’re willing to act on what we already know.Can kernicterus be reversed if caught early?

No. Once bilirubin has entered the brain tissue and caused damage, the injury is permanent. That’s why prevention is the only effective strategy. Early phototherapy or exchange transfusion can prevent damage from worsening, but they cannot undo what’s already happened. The goal is to stop the bilirubin from reaching the brain in the first place-by avoiding high-risk medications and treating jaundice promptly.

Are all antibiotics unsafe for jaundiced newborns?

No. Only specific drugs that displace bilirubin from albumin are risky. Penicillins like amoxicillin and cephalosporins like cefazolin are safe. Sulfonamides, ceftriaxone, and salicylates are the main concerns. Always confirm the antibiotic class with your provider. If they’re unsure, ask for the AAP guidelines on neonatal hyperbilirubinemia.

Is it safe to give sulfonamides if the baby’s bilirubin is normal?

Not necessarily. A “normal” bilirubin level can still be dangerous if albumin is low, if the baby is premature, or if they have acidosis. Some babies with bilirubin levels below the phototherapy threshold have still developed kernicterus after sulfonamide exposure. The risk isn’t just about the number-it’s about the balance between bilirubin, albumin, and the drug. When in doubt, avoid the drug.

Why are sulfonamides still approved if they’re so dangerous?

Sulfonamides are still approved because they’re effective against certain infections like urinary tract infections caused by specific bacteria, and they’re inexpensive. But their use in newborns is strictly limited. The FDA requires a black box warning on all sulfonamide packaging: avoid use in infants under 2 months. The issue isn’t approval-it’s misuse. Many providers aren’t trained on neonatal pharmacology risks, and guidelines aren’t always followed.

How can I know if my baby’s hospital follows safe medication practices?

Ask if they use the AAP’s 2022 guidelines for hyperbilirubinemia. Check if they have protocols that automatically flag high-risk medications when bilirubin levels are elevated. Hospitals with electronic health records should have built-in alerts. You can also ask if they screen for G6PD deficiency in at-risk infants. If they don’t have a written policy, it’s worth raising the question-your baby’s safety depends on it.

parth pandya

Man i read this and my head spun. Sulfonamides bad for jaundiced babies? I thought they were just for UTIs. My cousin’s kid got one last year and they didnt even check bilirubin. Hope he’s okay. Also i think i spelled something wrong again lol.

Albert Essel

This is one of the most meticulously researched posts I’ve seen on neonatal pharmacology. The distinction between jaundice and kernicterus is critical, and the data on albumin displacement is chilling. I especially appreciate the breakdown of alternative antibiotics-amoxicillin-clavulanate should be first-line everywhere, not just in affluent hospitals.

Charles Moore

It’s heartbreaking that we have the knowledge, the tools, and the guidelines-and yet, we still lose babies to this. It’s not about lack of science. It’s about access, training, and systemic neglect. In rural Ireland, we’ve seen similar issues with antibiotic misuse in newborns. We need more than alerts-we need mandatory neonatal pharmacology modules for all pediatric residents.

Gavin Boyne

So let me get this straight. We have a $0.05 drug that can blind or paralyze a baby, but we’re still using it because it’s cheaper than a $2.50 alternative? And we call this a healthcare system? I guess capitalism doesn’t care if your kid’s basal ganglia turn into a Jackson Pollock painting. #SulfonamideSlaughter

Rashi Taliyan

My heart is breaking reading this. I’m a nurse in Delhi and we get so many jaundiced babies-some with no screening at all. We give sulfa because it’s all we have. I cried after reading this. I didn’t know how dangerous it was. I’m going to start asking for albumin levels now. Thank you for writing this.

Kara Bysterbusch

The elegance of this exposition is not merely in its clinical precision but in its moral clarity. The notion that preventable neurological devastation is being traded for cost-efficiency is not merely a medical oversight-it is a societal betrayal. The imperative to adopt amoxicillin-clavulanate as standard of care is not a suggestion; it is an ethical obligation.

Francine Phillips

so like… sulfonamides bad? okay. got it. thanks for the info i guess.

Katherine Gianelli

I just want to say thank you to whoever wrote this. I’m a new mom and I didn’t know any of this. My baby was jaundiced and they gave him amoxicillin-I asked if it was safe and they said yes. I didn’t know to ask about albumin or G6PD. This post saved me from asking the wrong questions later. Please keep sharing stuff like this.

Joykrishna Banerjee

Typical Western medical colonialism. You all have EHRs and free bilirubin indices, but in India, we use sulfonamides because we don’t have your luxury of overdiagnosing and overtreating. Your 75% phototherapy threshold? Arbitrary. Our babies survive anyway. Maybe your system is the problem, not our pragmatism. 😒

Myson Jones

Great breakdown. I’m a pediatric resident in Ohio, and our hospital just rolled out the Epic alert last month. It’s a game-changer. One nurse told me she’d seen two cases of kernicterus in the last three years-and both involved sulfonamides. We’re finally catching up. It’s about time.

Rashmin Patel

As someone who works in maternal health in Mumbai, I’ve seen this too many times. Parents come in with a baby glowing yellow, and the doctor says, ‘It’s just jaundice, take this medicine.’ No screening, no albumin, no G6PD test. I’ve begged my colleagues to stop using sulfonamides. I’ve even printed out the AAP guidelines and taped them to the med cart. I’m not a hero-I’m just tired of seeing babies suffer because we’re too lazy to check a number.

sagar bhute

This post is a performative outrage. You think your guidelines are the only truth? What about traditional medicine? What about cultural context? You westerners think you know everything. In our villages, we use turmeric and sunlight. Maybe the real problem is your obsession with pharmaceuticals and blood tests. Your system is broken. Your babies are overtested. You’re creating problems to sell solutions.

Cindy Lopez

There is a grammatical inconsistency in the phrase 'that’s not a small effect.' The contraction should be followed by a comma if used parenthetically. Also, 'exchange transfusion' is hyphenated incorrectly in one instance. Minor, but it detracts from an otherwise excellent piece.