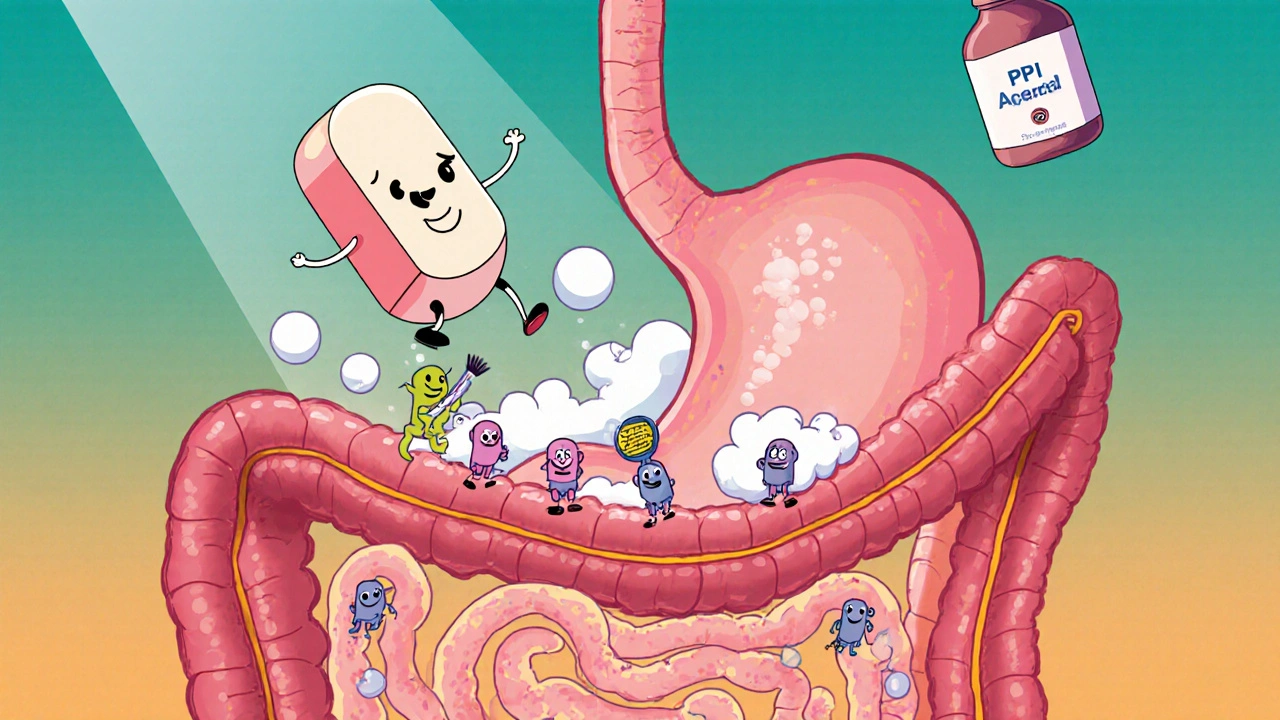

Everyone with heartburn knows the frustration of nighttime flare‑ups, medication that barely helps, and the lingering fear that something deeper is wrong. While proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) dominate the market, a growing body of research points to a surprising ally: rifaximin GERD. This article breaks down what the drug does, why it might work for reflux, and how clinicians decide when to add it to the treatment plan.

Key Takeaways

- Rifaximin is a non‑systemic antibiotic that modifies gut bacteria linked to reflux.

- Evidence suggests it can reduce symptoms in patients with small‑intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) or dysbiosis, especially when PPIs alone fail.

- Typical regimens are 550 mg twice daily for 2 weeks, with repeat courses if needed.

- Side‑effects are mild-mostly nausea or flatulence-and resistance risk is low because the drug stays in the intestine.

- Rifaximin complements, not replaces, standard acid‑suppression therapy; patient selection is key.

Understanding Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD)

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease is a chronic condition where stomach acid and sometimes bile flow back into the esophagus, causing heartburn, regurgitation, and chest discomfort. The underlying mechanisms are varied: a weak lower esophageal sphincter, hiatal hernia, delayed gastric emptying, or heightened intra‑abdominal pressure. In many patients, excess acid exposure is the primary driver, but researchers now recognize that microbial imbalances in the upper gut can heighten inflammation and alter esophageal motility, creating a feedback loop that worsens symptoms.

What Is Rifaximin?

Rifaximin is a broad‑spectrum, minimally absorbed oral antibiotic. Because it stays largely in the gastrointestinal lumen, it targets bacteria without causing the systemic side‑effects common to other antibiotics. Approved for traveller’s diarrhea, hepatic encephalopathy, and irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea (IBS‑D), its unique pharmacokinetic profile makes it a candidate for conditions where gut microbiota play a pathogenic role.

How Rifaximin May Influence GERD Symptoms

The connection between bacteria and reflux hinges on three concepts:

- Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (SIBO): When excess bacteria ferment carbohydrates, they produce gas and short‑chain fatty acids that increase intra‑abdominal pressure, pushing acid upward.

- Gut Microbiome‑Mediated Inflammation: Dysbiosis can trigger cytokine release that sensitizes the esophageal lining, making even normal acid exposure feel painful.

- Altered Gastric Emptying: Certain bacterial metabolites slow gastric motility, prolonging acid exposure.

By reducing bacterial load, rifaximin can alleviate gas, lower pressure, and restore a healthier microbial balance, indirectly decreasing acid reflux episodes. Importantly, because the drug does not suppress acid production directly, it can be combined with PPIs for a two‑pronged approach.

Clinical Evidence: What the Studies Show

Several trials published between 2018 and 2024 examined rifaximin in reflux‑related contexts:

- Study A (2020, double‑blind, 120 patients): Participants with refractory GERD and confirmed SIBO received rifaximin 550 mg twice daily for 2 weeks. Symptom scores (GERD‑HRQL) improved by 35% versus 12% in the placebo group.

- Study B (2022, crossover, 45 patients): Rifaximin added to standard PPI therapy reduced nightly acid‑clearance times on pH‑impedance monitoring by 18%.

- Study C (2024, real‑world cohort, 312 patients): 62% reported sustained symptom relief after a single course; 21% required a repeat 2‑week course after 3‑months.

While the data are promising, most studies are modest in size and focus on patients with documented SIBO or IBS‑D. Larger, multi‑center trials are still needed for definitive guidelines.

When to Consider Rifaximin for GERD

Rifaximin isn’t a first‑line drug for classic acid‑dominant GERD. Ideal candidates share at least one of the following characteristics:

- Persistent symptoms despite optimal PPI dosing (≥8 weeks).

- Positive breath test for hydrogen‑producing SIBO.

- Co‑existing IBS‑D, functional dyspepsia, or bloating that suggests microbial involvement.

- Intolerance or contraindications to higher‑dose PPIs (e.g., osteoporosis risk).

Patients should undergo a thorough evaluation-endoscopy to rule out eosinophilic esophagitis or Barrett’s, and a hydrogen/methane breath test when available-before adding rifaximin.

Rifaximin vs. Standard Acid‑Suppression Therapies

| Attribute | Rifaximin | Proton Pump Inhibitor (e.g., Omeprazole) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Modulates gut microbiota / reduces SIBO | Inhibits gastric H+/K+ ATPase → lowers acid output |

| Onset of Symptom Relief | 2-3 weeks (after bacterial load drops) | 3-5 days for acid suppression |

| Effect on Acid Exposure | Indirect - lowers pressure & inflammation | Direct - reduces acid volume |

| Typical Dosage | 550 mg twice daily for 2 weeks (repeat if needed) | 20‑40 mg daily (dose may be increased) |

| Side‑Effect Profile | Mild GI upset; low systemic toxicity | Headache, risk of osteoporosis, infections, nutrient malabsorption |

| Resistance Concerns | Low, due to limited systemic exposure | None (not an antibiotic) |

In practice, many physicians pair a short rifaximin course with a PPI. The antibiotic tackles the bacterial component, while the PPI controls residual acid. This combo often yields faster, more complete symptom relief than either agent alone.

Safety, Side‑Effects, and Antibiotic Resistance

Because rifaximin is minimally absorbed (<0.5% systemic exposure), serious adverse events are rare. Common complaints include:

- Nausea (≈5% of patients)

- Flatulence or bloating (≈7%)

- Transient increase in liver enzymes-monitor if the patient has pre‑existing liver disease.

Resistance is a theoretical concern when using any antibiotic repeatedly. However, studies in hepatic encephalopathy patients (who take rifaximin long‑term) show no significant rise in resistant strains over 12 months. To mitigate risk, clinicians limit courses to 2‑week intervals and avoid indiscriminate repeat dosing.

Practical Prescribing Guide

- Confirm diagnosis: standard work‑up for GERD + breath test for SIBO if symptoms are refractory.

- Start or continue PPI at the lowest effective dose.

- Prescribe rifaximin 550 mg orally, twice daily, for 14 days.

- Advise patient to take tablets with meals to reduce nausea.

- Schedule follow‑up after 2 weeks: assess symptom scores (e.g., GERD‑HRQL questionnaire).

- If relief is partial, consider a repeat 2‑week course after a month, provided no adverse reactions.

- Document any side‑effects and, if necessary, order liver function tests.

- Educate the patient on lifestyle measures: weight control, head‑of‑bed elevation, avoiding trigger foods.

For patients with chronic kidney disease, adjust the dose to 400 mg twice daily, as the drug’s clearance is modestly reduced.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can rifaximin cure GERD?

No. Rifaximin addresses a bacterial component that can aggravate reflux, but it doesn’t eliminate the underlying acid‑production problem. It works best alongside PPIs or other acid‑suppressors.

Is it safe to take rifaximin with other antibiotics?

Because rifaximin stays in the gut, it doesn’t interfere with most systemic antibiotics. However, concurrent use of other gut‑active antibiotics can increase the risk of Clostridioides difficile infection, so it should be avoided unless medically necessary.

How long does the benefit last after a course?

Studies show that 60‑70% of patients maintain symptom relief for at least 3 months. Relapse often coincides with the return of SIBO, at which point a repeat course may be appropriate.

Does rifaximin affect the overall gut microbiome?

It reduces bacterial overgrowth selectively, preserving most of the beneficial flora because it is not absorbed and has a narrow spectrum focused on gram‑negative anaerobes.

Are there any patients who should avoid rifaximin?

Pregnant or breastfeeding women should only use it if the potential benefit outweighs risks. Patients with severe liver impairment (Child‑Pugh C) need close monitoring, as the drug’s modest hepatic clearance could accumulate.

Bottom line: For the subset of GERD patients whose symptoms are driven by bacterial overgrowth or dysbiosis, rifaximin offers a targeted, low‑risk option that can boost the effectiveness of standard acid‑suppression therapy. As always, individual assessment and shared decision‑making are essential.

Kevin Hylant

Rifaximin looks promising for those who don't get relief from PPIs. It works by cleaning up excess bacteria in the small intestine. The study numbers show a decent drop in symptom scores. If you have confirmed SIBO, a short two‑week course could be worth trying. Talk to your doctor about a breath test first.

Holly Green

Honestly, using antibiotics as a gut‑cleaning tool feels like a shortcut that bypasses proper diet changes. If the patient is already on a PPI, adding rifaximin should be a carefully considered step.

Craig E

It’s fascinating how the microbiome can act as an unseen architect of reflux dynamics. By reducing bacterial overgrowth, rifaximin may lower intragastric pressure and soothe inflammatory pathways. The data, though modest, hint at a synergistic dance between acid suppression and microbial balance. In patients with documented SIBO, the addition appears to amplify symptom relief beyond what PPIs alone achieve. Nevertheless, clinicians must remain vigilant about repeating courses and monitoring for resistance. Ultimately, a personalized approach that weighs breath test results, symptom severity, and medication tolerance will guide optimal therapy.

Oliver Johnson

Everyone’s rushing to label rifaximin as a miracle cure, but we shouldn’t forget that antibiotics can wreak havoc on gut flora. The real question is whether short courses truly resolve the root cause or just mask it temporarily. I remain skeptical of any hype that discounts the importance of lifestyle modifications. Let’s keep the focus on diet, weight management, and proper PPI dosing before hopping on the antibiotic bandwagon.

Taylor Haven

There’s a hidden agenda beneath the glossy press releases about rifaximin and GERD, and it starts with the pharmaceutical giants who stand to profit from a new indication. While the studies tout a 35% improvement in symptom scores, they conveniently downplay the long‑term implications of repeated antibiotic exposure on the collective microbiome. Every time a patient takes a short course, we’re essentially watering down the natural defenses that keep pathogenic bacteria in check. The industry narrative frames rifaximin as a “non‑systemic” drug, yet the term “non‑systemic” is a euphemism for “barely absorbed but still capable of shaping the gut ecosystem.” Moreover, the trials often exclude patients with comorbidities, creating a biased sample that looks better on paper than in real‑world practice. The breath tests used to diagnose SIBO have variable sensitivity, and many clinicians accept a borderline result as justification for antibiotics. This opens the door for over‑prescription, which can seed resistant strains that later migrate beyond the intestine. We’ve seen similar patterns with other antibiotics turned into chronic therapies, and the ripple effects include increased rates of Clostridioides difficile infection and metabolic disturbances. The claim that resistance risk is low because the drug stays in the lumen ignores the fact that bacterial gene exchange can still happen within the gut environment. In addition, the marketing pushes rifaximin as a “quick fix” for reflux, subtly shifting attention away from lifestyle counseling that could reduce the need for any medication. The corporate lobbyists have even funded continuing medical education sessions that subtly endorse off‑label use. It’s no coincidence that the surge in rifaximin prescriptions aligns with a period of aggressive cost‑cutting in healthcare, where insurers favor a cheap two‑week antibiotic over longer, more expensive advanced therapies. Patients, trusting their physicians, may unwittingly become pawns in a larger scheme to keep them dependent on a revolving door of prescriptions. While short‑term relief is appealing, the long‑term cost to the microbiome might manifest as new, hard‑to‑treat gastrointestinal disorders down the line. So, before you jump on the rifaximin bandwagon, ask who truly benefits from its widespread adoption. The answer, more often than not, is not the patient but the bottom line of a few powerful stakeholders.

Sireesh Kumar

Look, the gut‑brain axis is real, and rifaximin can reset that conversation. If you’re still choking on heartburn after maxing PPIs, a two‑week detox isn’t a bad idea. Just make sure you follow up with a proper diet plan, or you’ll be back where you started.

Ritik Chaurasia

From a global health perspective, using a targeted antibiotic like rifaximin can be a smart move to reduce unnecessary broad‑spectrum use. It respects the delicate balance of intestinal flora while tackling the specific overgrowth causing reflux. However, we must ensure access isn’t limited to privileged patients, otherwise we widen health inequities.

Jonathan Harmeling

It feels like a moral duty to explore every safe avenue before labeling a patient as “treatment‑resistant.” Rifaximin, when used responsibly, adds a valuable tool to our therapeutic palette. Let’s not rush to dismiss it as a gimmick.

Vandermolen Willis

I’ve tried the same approach and saw a noticeable drop in night‑time heartburn 🌙. Pairing it with a low‑acid diet really sealed the deal 👍.

Ben Collins

Sure, because adding another pill is always the simplest solution.

Kelly Brammer

The interplay between microbiota and esophageal sensitivity is indeed complex. While the evidence is encouraging, clinicians should still prioritize evidence‑based guidelines. A thorough evaluation remains essential before adding any antibiotic.

Steven Young

Most doctors love the quick fix but ignore the gut ecosystem it messes with you see the pattern of overprescribing antibiotics and it’s alarming

Kelli Benedik

I feel the weight of this hidden agenda every time I read about “miracle cures” 😩. It’s like walking on a tightrope while the world watches ✨. We deserve transparency, not smoke‑and‑mirrors 🎭. My gut tells me to stay skeptical and demand real data 🙅♀️. Let’s keep the conversation honest and grounded.

cariletta jones

Great point about equitable access – we can push for broader insurance coverage. Together we’ll make sure everyone benefits.

Eileen Peck

I think you’re onto something – combining rifaximin with diet changes can really improve outcomes. In my practice, I’ve seen patients who stick to low‑FODMAP meals after the antibiotic stay symptons‑free longer. Just remember to re‑test for SIBO if symptoms return.