TZD Fluid Retention Risk Calculator

Your Risk Assessment

When you’re managing type 2 diabetes, finding a medication that lowers blood sugar without causing dangerous side effects is critical. That’s where thiazolidinediones come in - drugs like pioglitazone (Actos) and rosiglitazone (Avandia) that make your body respond better to insulin. But here’s the catch: for some people, these drugs can cause fluid buildup so severe it triggers or worsens heart failure. It’s not a rare side effect. It’s common enough that doctors now treat it like a red flag.

How Thiazolidinediones Work - and Why They Cause Fluid Retention

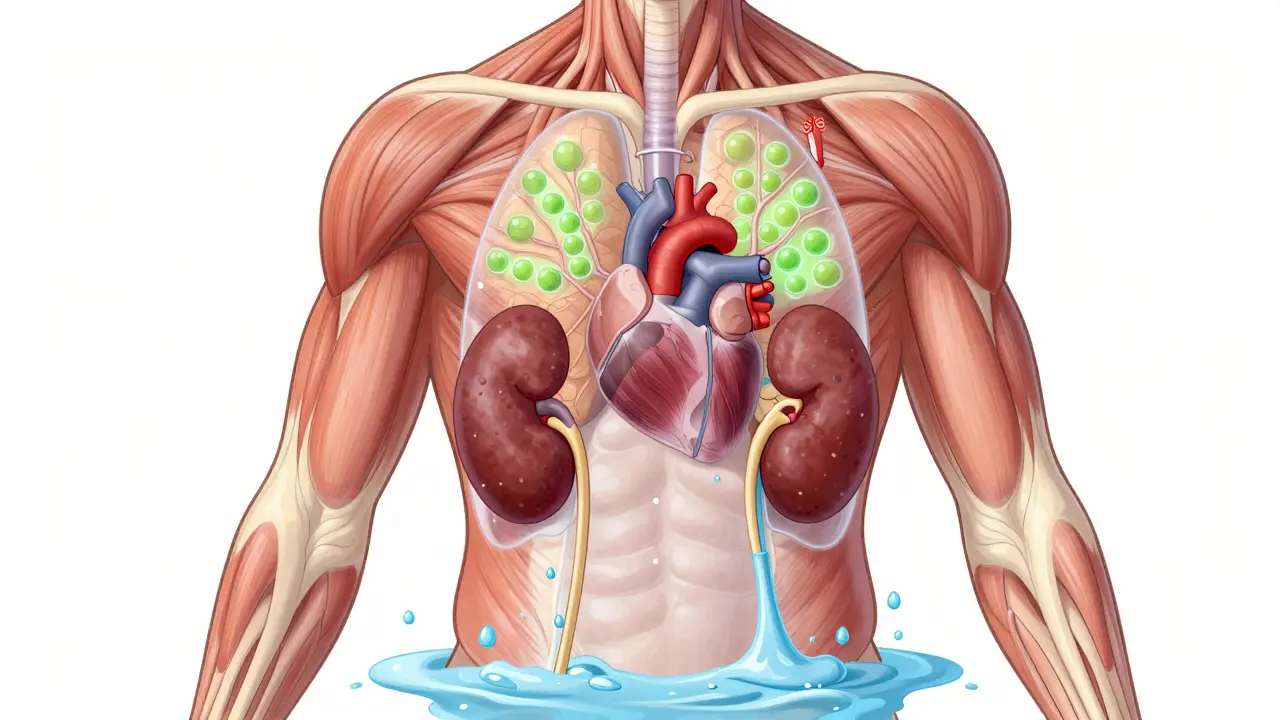

Thiazolidinediones, or TZDs, activate a protein in your body called PPAR-γ. This helps fat and muscle cells take up glucose more efficiently, which lowers blood sugar. But PPAR-γ isn’t just in fat and muscle. It’s also in your kidneys, blood vessels, and heart. That’s where the trouble starts.

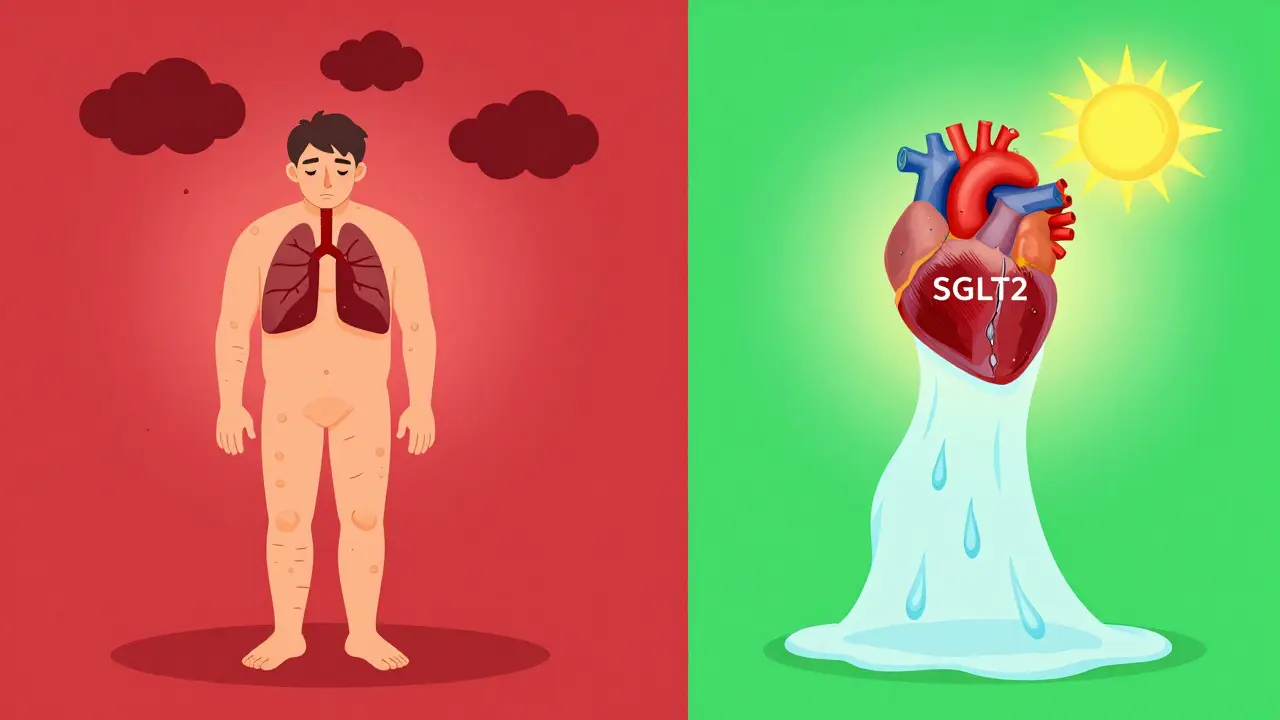

When TZDs hit the kidneys, they tell the tubules to hold onto more sodium and water. This isn’t a minor effect. Studies show these drugs can increase blood volume by 6-7% in healthy people. That extra fluid doesn’t just sit around - it leaks into tissues, causing swelling in the ankles and legs (peripheral edema). In some cases, it floods the lungs, leading to shortness of breath and pulmonary edema.

The exact mechanism is still debated. Some research points to SGK-1, a kidney enzyme that boosts sodium reabsorption. Others suggest TZDs interfere with chloride transport or activate alternative sodium channels. What’s clear is that this isn’t just a side effect - it’s a direct pharmacological action. And it happens in 5-15% of users, depending on whether they’re on insulin too.

Who’s at Risk - And Who Should Avoid TZDs Completely

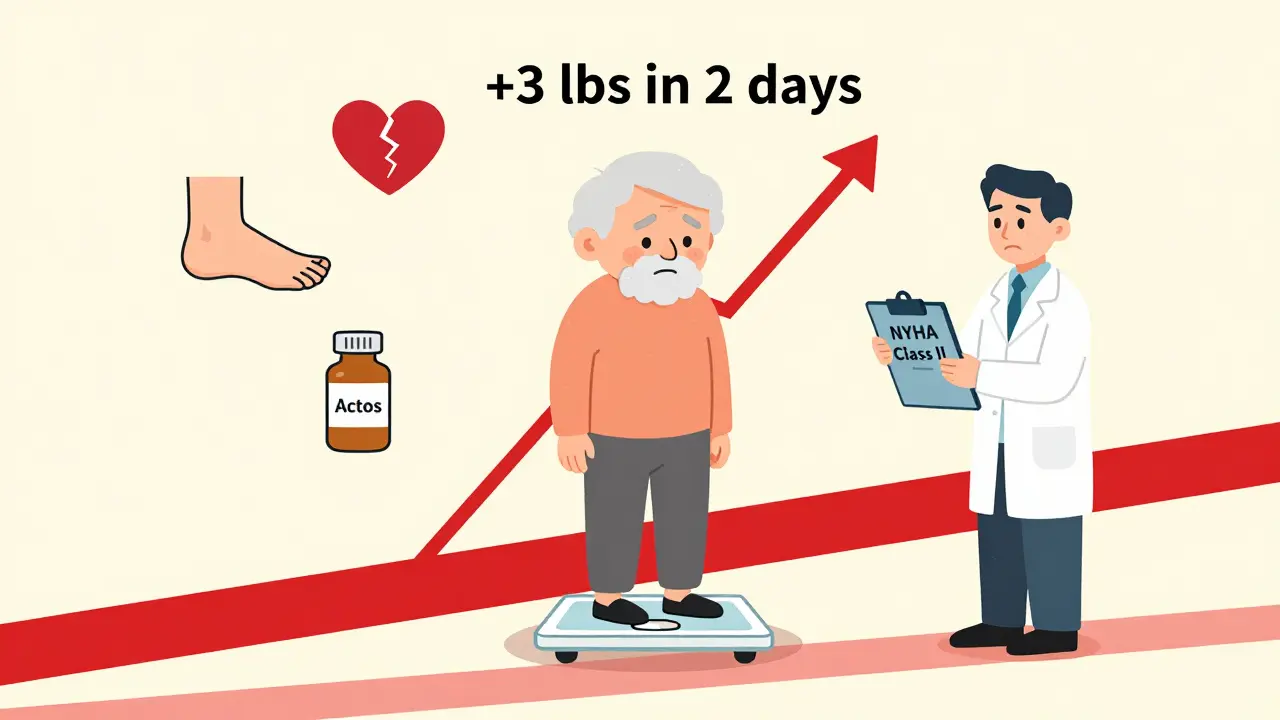

If you have heart failure, TZDs are not an option. The FDA’s black box warning is blunt: don’t use them if you have NYHA Class III or IV heart failure. That means you’re already struggling to breathe at rest, or you can’t walk a block without getting winded.

But here’s the scary part: many patients who are taking TZDs already have heart failure - and don’t know it. A 2018 analysis of over 424,000 U.S. diabetic patients found that 40.3% of those on TZDs had either a heart failure diagnosis, an ejection fraction under 40%, or were on loop diuretics. That’s nearly half of all TZD users with clear signs of heart disease. And yet, they’re still on these drugs.

Women are more likely to develop fluid retention than men. So are people taking insulin. If you’re on both TZDs and insulin, your risk of swelling jumps to about 15%. Age matters too - most TZD users are over 65. And if you’re obese, especially with class 3 obesity, your heart is already under strain. Adding a drug that increases blood volume? That’s stacking the deck.

What Happens When Fluid Retention Turns Into Heart Failure

Fluid retention from TZDs doesn’t always start with swollen ankles. Sometimes, it begins quietly: a little more fatigue, a shirt that feels tighter, needing to prop up your legs at night. Then, over weeks, you gain 10 pounds or more - not from eating more, but from water.

In one study of 111 diabetic patients with existing heart failure, 17% developed new fluid retention on TZDs. Six of them had worsening jugular venous distension - a sign the heart can’t pump blood back effectively. Two developed full-blown pulmonary edema. And here’s the kicker: the severity of their heart failure before starting TZDs didn’t predict who would crash. It was unpredictable. Even patients with mild heart failure could deteriorate.

What makes this worse is that loop diuretics - the usual go-to for fluid overload - often don’t work well against TZD-induced retention. The fluid buildup resists treatment. The only reliable fix? Stopping the drug. Within days to weeks, the swelling goes down. The lungs clear. The heart recovers. But if you keep taking it, the damage can become permanent.

Current Guidelines - What Doctors Are Supposed to Do

The American Diabetes Association and the American Heart Association agree: TZDs should be used with extreme caution. They’re not banned. But they’re not first-line anymore. Here’s what they recommend:

- Avoid TZDs entirely in patients with NYHA Class III or IV heart failure.

- If you have Class I or II heart failure - mild symptoms, only during activity - consider TZDs only if no other options work, and only with close monitoring.

- Check weight weekly for the first month. A gain of more than 2-3 pounds in a week is a warning sign.

- Look for new or worsening edema, shortness of breath, or fatigue.

- Discontinue immediately if fluid retention develops, even if it’s mild.

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists is even stricter: they recommend avoiding TZDs in anyone with heart failure or at high risk - period. That’s because the data shows so many patients on TZDs already have hidden heart disease. It’s not worth the gamble.

Why Are TZDs Still Prescribed?

If the risks are this high, why do 8.3% of diabetic patients still take them? The answer lies in what they do well.

TZDs are one of the few oral diabetes drugs that don’t cause low blood sugar on their own. They improve insulin sensitivity for months, sometimes years. They may also lower triglycerides and raise HDL (good cholesterol). Some studies suggest pioglitazone might reduce plaque buildup in arteries.

For a 70-year-old man with type 2 diabetes, coronary disease, and no heart failure, who’s struggling with high HbA1c despite metformin and SGLT2 inhibitors, TZDs can be a last-resort option. But only if the doctor knows the full picture - and monitors like a hawk.

Still, the market has shrunk. Rosiglitazone is now only available through a restricted program after a 2007 study linked it to increased heart attacks. Pioglitazone remains on the market, costing around $300 for a 30-day supply. But its use is declining. Newer drugs like GLP-1 agonists and SGLT2 inhibitors offer better safety profiles - with actual heart protection, not just blood sugar control.

What You Should Do If You’re on a TZD

If you’re taking pioglitazone or rosiglitazone, here’s your action plan:

- Know your heart health. Ask your doctor for your ejection fraction if you haven’t had an echocardiogram in the last year.

- Track your weight daily. A sudden gain of 3+ pounds in 2 days? Call your doctor.

- Watch for swelling in your ankles, belly, or hands. Notice if your rings feel tight or your shoes hurt.

- Don’t ignore shortness of breath - even if it’s just climbing stairs.

- Ask if there’s a safer alternative. SGLT2 inhibitors (like empagliflozin) and GLP-1 agonists (like semaglutide) reduce heart failure risk, not increase it.

Don’t stop the drug on your own. But do speak up. Many patients assume swelling is just aging or being overweight. It’s not. It’s a signal.

The Bigger Picture

Thiazolidinediones are a reminder that drugs don’t exist in isolation. They affect multiple systems. What helps one organ can hurt another. In this case, improving insulin sensitivity comes at the cost of fluid balance - and for people with heart disease, that trade-off is deadly.

The science behind TZD-induced fluid retention is still evolving. New studies suggest vascular leakage and nitric oxide changes may also play a role. But we don’t need to wait for more answers. We already know enough to act.

If you have diabetes and heart failure - or even just risk factors like high blood pressure, obesity, or kidney disease - TZDs are not your friend. There are better, safer tools now. Ask your doctor what they are. Your heart will thank you.

Marlon Mentolaroc

Yo, I’ve seen this play out in clinic-old guy on pioglitazone, gains 12 lbs in 10 days, thinks he’s ‘just getting chubby.’ Then he shows up panting on the couch. Docs miss it because the symptoms sneak in like a ghost. TZDs are the quiet killer of diabetic patients who don’t even know they’re already heart-failed.

siva lingam

so tzds cause water weight ok cool so does eating bread but no one screams about bread

Patrick Gornik

Let’s deconstruct the hegemony of pharmacological reductionism. TZDs don’t merely cause fluid retention-they expose the ontological fracture between metabolic optimization and systemic integrity. We fetishize HbA1c like it’s a divine number, ignoring that biology is not a spreadsheet. The kidney isn’t a faucet to be turned; it’s a symphony of ion channels, hormonal feedback loops, and evolutionary compromises. When we force PPAR-γ activation, we’re not treating diabetes-we’re conducting a biochemical coup d’état on homeostasis. And the collateral damage? It’s not a side effect. It’s the price of our hubris.

Meanwhile, SGLT2 inhibitors? They don’t just lower glucose-they trigger natriuresis, reduce cardiac preload, and improve mitochondrial efficiency. They don’t fix a symptom. They restore equilibrium. The real question isn’t whether TZDs are dangerous. It’s why we ever thought they were acceptable in the first place.

Izzy Hadala

While the clinical evidence regarding TZD-induced fluid retention is robust, particularly in patients with pre-existing cardiac dysfunction, the underlying molecular pathways remain incompletely elucidated. Recent studies suggest that PPAR-γ activation may modulate renal epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) expression via serum- and glucocorticoid-inducible kinase 1 (SGK1), leading to sodium hyperreabsorption. Additionally, altered endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) activity may contribute to capillary permeability. Further research into tissue-specific PPAR-γ isoforms may yield more targeted therapeutic strategies that preserve insulin sensitization without compromising cardiovascular homeostasis.

Shelby Marcel

wait so u mean like… my ankles been swellin for 3 months and its not just ‘cause i sit too much??

Juan Reibelo

I’ve had patients on pioglitazone for years-no issues. Then, one winter, they gain 8 pounds, start waking up gasping, and suddenly, it’s a full-blown emergency. It’s not that the drug is evil. It’s that we stopped listening. We stopped asking about weight changes. We stopped checking for edema. We got lazy. And now we’re surprised when the body screams back?

Doctors need to treat this like a vital sign-not an afterthought. Weight tracking isn’t optional. It’s mandatory. And if your patient is on TZDs and hasn’t had an echo in a year? You’re not managing care. You’re gambling.

Heather McCubbin

THEY KNOW THIS IS DANGEROUS AND THEY STILL SELL IT TO OLD PEOPLE BECAUSE PHARMA MAKES BILLIONS AND NO ONE CARES UNTIL SOMEONE DIES

MY GRANDPA WAS ON THIS DRUG FOR 5 YEARS AND NO ONE TOLD HIM HIS HEART WAS FAILING UNTIL HE COULDN’T WALK TO THE BATHROOM

THEY WANT YOU TO THINK IT’S JUST ‘SIDE EFFECTS’ BUT IT’S NOT IT’S A COVER-UP

WHY AREN’T WE PROTESTING THIS

Phil Maxwell

I’ve been on pioglitazone for 3 years. No swelling. No shortness of breath. Just steady HbA1c around 6.2. I guess I’m one of the lucky ones? Still, I check my weight every morning. I’ve learned to pay attention. Not because I’m paranoid-because I’ve seen what happens when you don’t.

Shanta Blank

So let me get this straight… you’re telling me a drug that makes my body use insulin better… also floods my lungs like I’m drowning in a bathtub? And they still sell it? Like it’s a discount coupon for diabetes?

I’d rather have diabetic ketoacidosis than wake up choking on my own fluids. At least then I’d know it was coming.

My cousin’s mom died on this. She thought the puffiness was ‘just aging.’ She was 68. She didn’t even know she had heart disease until they put her in the ICU.

How many people are still on this? How many are dying quietly? I’m not even mad. I’m just… numb.

Dolores Rider

you know what’s scary? the FDA knew this was happening… and still let it stay on the market… it’s not an accident… it’s a business decision. they don’t care if you die… they care if you keep buying. i’ve seen the emails. they call it ‘manageable risk.’

you think your doctor’s looking out for you? they’re paid by pharma reps who bring donuts and free samples. ask them if they’ve ever been to a pioglitazone safety meeting. they’ll change the subject.

i’m not paranoid. i’m just the person who read the damn studies.

Tiffany Wagner

my doc put me on pioglitazone after metformin gave me the runs… i didn’t realize the swelling was a problem until my shoes hurt… now i’m off it… and honestly? i feel lighter. like my body remembered how to breathe.

no drama. no yelling. just… i stopped gaining weight. and now i can walk up stairs without stopping.

blackbelt security

Don’t let fear silence your questions. If you’re on a TZD, you have the right to demand an echo. To track your weight. To ask about alternatives. This isn’t weakness-it’s strength. Your heart is your most important organ. Protect it like your life depends on it-because it does.

Tommy Sandri

In the context of global diabetes management, the continued use of thiazolidinediones reflects broader systemic challenges in pharmaceutical regulation, physician education, and patient advocacy. While newer agents offer superior cardiovascular safety profiles, access and affordability remain barriers in many regions. In low-resource settings, TZDs remain a cost-effective option for insulin sensitization. However, this must be paired with mandatory cardiac screening protocols. The ethical imperative is not to ban TZDs outright, but to ensure their use is informed, monitored, and equitable.